There is no doubt that this was a tough year by any measure. The news, in my country and around the world. was depressing, scary and, at times, downright ridiculous. Personally, I had some very high highs and some very low lows. The summer was particularly hot and oppressive. And this semester was unusually demanding at work. More than any other year I can remember, I took solace and comfort by retreating into my books. I have listed here the books, essays and translations that kept me busy in 2018. War and Peace, Daniel Deronda, The Divine Comedy and Stach’s three volume biography of Kafka were particular favorites, but there really wasn’t a dud in this bunch.

Classic Fiction and Non-Fiction (20th Century or earlier):

War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy (trans. Louise and Alymer Maude)

The Bachelors by Adalbert Stifter (trans. David Bryer)

City Folk and Country Folk by Sofia Khvoshchinskaya (trans. Nora Seligman Favorov)

The Juniper Tree by Barbara Comyns

The Mill on the Floss by George Eliot

The Warden by Anthony Trollope

A Dead Rose by Aurora Caceres (trans. Laura Kanost)

Nothing but the Night by John Williams

G: A Novel by John Berger

Two Serious Ladies by Jane Bowles

Artemisia by Anna Banti (trans. Shirley D’Ardia Caracciolo)

The Ballad of Peckham Rye by Muriel Spark

Flesh by Brigid Brophy

The Portrait of a Lady by Henry James

A Handful of Dust by Evelyn Waugh

The Colour of Memory by Geoff Dyer

The Brothers Karamazov by Dostoevsky (trans. by Ignat Avsey)

Daniel Deronda by George Eliot

Lyric Novella by Annmarie Schwarzenbach (trans. Lucy Renner Jones)

The Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri (trans. Allen Mandelbaum)

The Achilleid by Statius (trans. Stanley Lombardo)

The Life and Opinions of Zacharias Lichter by Matei Calinescu (trans. Adriana Calinescu and Breon Mitchell)

The Blue Octavo Notebooks by Franz Kafka (trans. Ernst Kaiser and Eithne Wilkins)

Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter by Simone de Beauvoir (trans. James Kirkup)

Journey into the Mind’s Eye: Fragments of an Autobiography by Lesley Blanch

String of Beginnings by Michael Hamburger

Theseus by André Gide (trans. John Russell)

Contemporary Fiction and Non-Fiction:

Kafka: The Early Years by Reiner Stach (trans. Shelley Frisch)

Kafka: The Decisive Years by Reiner Stach (trans. Shelley Frisch)

Kafka: The Years of Insight by Reiner Stach (trans. Shelley Frisch)

Villa Amalia by Pascal Quignard (trans. Chris Turner)

All the World’s Mornings by Pascal Quignard (trans. James Kirkup)

Requiem for Ernst Jundl by Friederike Mayröcker (trans. Roslyn Theobald)

Bergeners by Tomas Espedal (trans. James Anderson)

Kudos by Rachel Cusk

The Cost of Living by Deborah Levy

The Years by Annie Ernaux (trans. Alison L. Strayer)

He Held Radical Light by Christian Wiman

The Unspeakable Girl by Giorgio Agamben and Monica Ferrando (trans. Leland de la Durantaye)

The Adventure by Giorgio Agamben (trans. Lorenzo Chiesa)

Essays and Essay Collections:

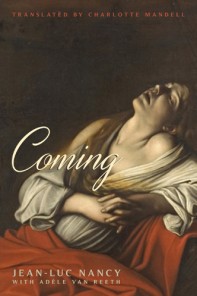

Expectations by Jean-Luc Nancy

Errata by George Steiner

My Unwritten Books by George Steiner

The Poetry of Thought by George Steiner

A Handbook of Disappointed Fate by Anne Boyer

“Dante Now: The Gossip of Eternity” by George Steiner

“Conversation with Dante” by Osip Mandelstam

“George Washington”, “The Bookish Life,” and “On Being Well-Read” and “The Ideal of Culture” by Joseph Epstein

“On Not Knowing Greek,” “George Eliot,” “Russian Thinking” by Virginia Woolf

Poetry Collections:

The Selected Poems of Donald Hall

Exiles and Marriage: Poems by Donald Hall

H.D., Collected Poems

Elizabeth Jennings, Selected Poems and Timely Issues

Eavan Boland, New Selected Poems

Omar Carcares, Defense of the Idol

The Complete Poems of Anna Akhmatova

Analicia Sotelo, Virgin

Elizabeth Bishop, Poems, Prose and Letters (LOA Edition)

Michael Hamburger: A Reader, (Declan O’Driscoll, ed.)

I also dipped into quite a few collections of letters such as Kafka, Kierkegaard, Kleist, Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, etc. that I won’t bother to list here. I enjoyed reading personal letters alongside an author’s fiction and/or biography.

My own Translations (Latin and Greek):

Vergil, Aeneid IV: Dido’s Suicide

Statius, Silvae IV: A Plea for Some Sleep

Horace Ode 1.5: Oh Gracilis Puer!

Horace, Ode 1.11: May You Strain Your Wine

Propertius 1.3: Entrusting One’s Sleep to Another

Seneca: A Selection from “The Trojan Women”

Heraclitus: Selected Fragments

Cristoforo Landino, Love is not Blind: A Renaissance Latin Love Elegy

As George Steiner writes in his essay Tolstoy or Dostoevsky: “Great works of art pass through us like storm-winds, flinging open the doors of perception, pressing upon the architecture of our beliefs with their transforming powers. We seek to record their impact, to put our shaken house in its new order.” My reading patterns have most definitely changed and shifted this year. I am no longer satisfied to read a single book by an author and move on. I feel the need to become completely absorbed by an author’s works in addition to whatever other sources are available (letters, essays, biography, autobiography, etc.) Instead of just one book at a time, I immerse myself in what feels more like reading projects. I am also drawn to classics, especially “loose, baggy monsters” and have read very little contemporary authors this year. I image that this pattern will continue into 2019.

Anne Hidden, Quignard’s protagonist in Villa Amalia, is a musician and composer who has made a name for herself by condensing, paring down, and reinventing scores of music. He writes about her process:

Anne Hidden, Quignard’s protagonist in Villa Amalia, is a musician and composer who has made a name for herself by condensing, paring down, and reinventing scores of music. He writes about her process:

Monsieur de Sainte Colombe, a virtuoso viol player and teacher in seventeenth-century France, is a man of extremes: he practices his instrument for extensive, solitary hours, he rejects any attention or spotlight for his talents, and he still feels a deep, passionate love for his long-deceased wife. When the novella begins, Colombe’s wife has died but his feelings for her have not faded in the least: “Three years after her death, her image was still before him. After five years, her voice was still whispering in his ears.” He becomes a recluse and music becomes the center of his life: “Sainte Colombe henceforward kept to his house and dedicated his life to music. Year after year he labored at the viol and became an acknowledged master. In the two years following his wife’s death he worked up to fifteen hours a day.”

Monsieur de Sainte Colombe, a virtuoso viol player and teacher in seventeenth-century France, is a man of extremes: he practices his instrument for extensive, solitary hours, he rejects any attention or spotlight for his talents, and he still feels a deep, passionate love for his long-deceased wife. When the novella begins, Colombe’s wife has died but his feelings for her have not faded in the least: “Three years after her death, her image was still before him. After five years, her voice was still whispering in his ears.” He becomes a recluse and music becomes the center of his life: “Sainte Colombe henceforward kept to his house and dedicated his life to music. Year after year he labored at the viol and became an acknowledged master. In the two years following his wife’s death he worked up to fifteen hours a day.”

Time and Space are the focus of Berger’s brief yet lovely writings in this impossible-to-classify book. Part one, entitled “Once” is an attempt to capture the enigmatic, human experience of time while part two, entitled “Here” explores the concept of space especially in relation to sight and distance. The text feels like a series of snapshots into Berger’s mind as he uses art, photography, philosophy, poetry and personal anecdotes to grapple with time and space; Hegel, Marx, Dante, Camus, Caravaggio are just a few of the artists and thinkers that are given fleeting attention in his text.

Time and Space are the focus of Berger’s brief yet lovely writings in this impossible-to-classify book. Part one, entitled “Once” is an attempt to capture the enigmatic, human experience of time while part two, entitled “Here” explores the concept of space especially in relation to sight and distance. The text feels like a series of snapshots into Berger’s mind as he uses art, photography, philosophy, poetry and personal anecdotes to grapple with time and space; Hegel, Marx, Dante, Camus, Caravaggio are just a few of the artists and thinkers that are given fleeting attention in his text. Caravaggio’s

Caravaggio’s