“One unquenchable longing has the mastery of me, which hitherto I neither would nor could repress; ’tis an insatiable craving for books, although, perhaps I have more than I ought.” —Francesco Petrarch

I had the chance today to visit one of my favorite bookstores in New England. Located in a small, shoreline community, it actually has five different locations spread throughout the town. I only managed to visit two of the five locations today and even that took me a few hours. The main store is a large, old farmhouse with a series of barns on the property, all filled from floor to ceiling with books. None of the barns are heated so it was a bit rough going on this cold, wet day. But, in the end, (even though I was cold and drenched and looked like a wet poodle) it was totally worth the trip. Here is my haul:

Poetry:

I’ve become quite fond of collecting the Library of America editions—they look rather handsome on one’s shelves. I have been making a concerted effort to read more American authors, so this LOA edition of 17th and 18th century poetry was a great find. I was also pleased to add more Michael Hamburger, Marianne Moore and C.P. Cavafy to my poetry collection. The “Diaries of Exile,” translated from the Modern Greek and published by Archipelago Books, was also a pleasant find.

Essays:

I was so thrilled to find another George Steiner collection of essays that I don’t own, as well as another volume of Joseph Epstein essays. The J.M. Coetzee essays look intriguing—topics include Cees Nooteboom, Translating Kafka, Robert Musil’s Diaries, Dostoevsky and the essays of Joseph Brodsky, just to name a few. I already owned the paperback version of Michael Schmidt’s Lives of the Poets, and I was excited to upgrade to this hard copy edition that is in perfect condition. Lord’s The Singer of Tales is a nice addition to my classics library as it deals with the orality of Homeric poetry. And finally, the Hamburger and Colin Wilson essays will be a nice additions (or editions) to my shelves.

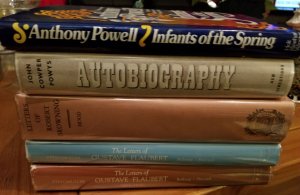

Autobiography and Letters:

I am especially excited about this stack. I’ve already started reading John Cowper Powys’s novels and I upgraded to this hard copy edition of his Autobiography. My Powys reading project will take me into 2019. I am also planning an Anthony Powell reading project for the new year and was exited to find this first volume of his autobiography. I own a copy of the first volume of Flaubert Letters which is in tatters, so not only did I get a copy in perfect condition but I also found a copy of the second volume. Finally, I found a wonderful early, hard copy edition (Yale Press, 1933, collected by Thomas J. Wise) of Robert Browning’s Letters.

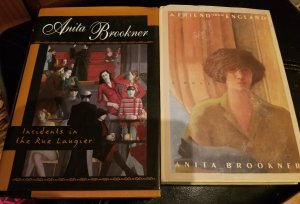

Fiction:

Finally, I did manage to buy some fiction as well. I want to read Anita Brookner in the new year. I already have one of her books sitting on my shelves so these two will be nice additions.

Bonus: Today’s Book Mail

I’ve also become captivated by Andre Gide’s writing and these two gems arrived today in the mail. (I thought my family was going to have a fit when I arrived home with all of these books and there were also more books waiting for me in the post!) I am planning to explore Gide in the new year and I am also awaiting a copy of his Journals which I have already sampled and am eager to dive into.

As Petrarch says, perhaps I have more than I ought?

It doesn’t matter, I will still collect books and read them anyway.

(For what it’s worth I did cull three large bags of books from my shelves today so, overall, I broke even.)

William Gass astutely describes the literary style of Henry James, “If any of us were as well taken care of as the sentences of Henry James, we would never long for another, never wander away; where else would we receive such constant attention, our thoughts anticipated, our feelings understood?” As I was struggling to decide which title on my list of

William Gass astutely describes the literary style of Henry James, “If any of us were as well taken care of as the sentences of Henry James, we would never long for another, never wander away; where else would we receive such constant attention, our thoughts anticipated, our feelings understood?” As I was struggling to decide which title on my list of  Published in 1948, Nothing but the Night is John Williams’s, little known about, first novel. It takes place over the course of a single day in the life of twenty-three year old Arthur Maxley who has suffered a very traumatic experience in his childhood. When we first meet Arthur, he is alone in his apartment—he is most often alone—and after a night of solitary drinking and reading is just waking up from a dream. The story is intense and suspenseful from the very beginning as Williams slowly reveals the tragedy Arthur has suffered in his early life. By slowing down time in his narrative, we are given a realistic glimpse into Arthur’s fractured and damaged mind. For instance, Arthur forces himself to get out of bed and take a walk in the park, but never actually makes it to the park because he goes into at a seedy diner. The vivid and startling description of his breakfast is a clue that Arthur is truly suffering:

Published in 1948, Nothing but the Night is John Williams’s, little known about, first novel. It takes place over the course of a single day in the life of twenty-three year old Arthur Maxley who has suffered a very traumatic experience in his childhood. When we first meet Arthur, he is alone in his apartment—he is most often alone—and after a night of solitary drinking and reading is just waking up from a dream. The story is intense and suspenseful from the very beginning as Williams slowly reveals the tragedy Arthur has suffered in his early life. By slowing down time in his narrative, we are given a realistic glimpse into Arthur’s fractured and damaged mind. For instance, Arthur forces himself to get out of bed and take a walk in the park, but never actually makes it to the park because he goes into at a seedy diner. The vivid and startling description of his breakfast is a clue that Arthur is truly suffering: When I mentioned on Twitter that I was going to read my first Jane Bowles story, there was a rather strong, positive reaction to her writing. But the comments I received about Two Serious Ladies still did not prepare me for reading this story. This short novel, in fact her only one, is enigmatic, humorous, surprising, even shocking and sad all at the same time. Truman Capote’s description of the story, I think, sums it up best:

When I mentioned on Twitter that I was going to read my first Jane Bowles story, there was a rather strong, positive reaction to her writing. But the comments I received about Two Serious Ladies still did not prepare me for reading this story. This short novel, in fact her only one, is enigmatic, humorous, surprising, even shocking and sad all at the same time. Truman Capote’s description of the story, I think, sums it up best: