Aira’s novella has three distinct parts to it, all of which display his masterful ability to play with time in his narrative. The story begins with a sixteen-year-old girl named Marcia walking down a street in Flores, observing other young people talking, hanging out and listening to music. Marcia, a self-conscious, over-weight, slightly depressed, is shocked yet excited when two punk girls named Mao and Lenin yell out to her, “Wanna fuck.” Aira’s chronicle of Marcia moving through the crowd of teenagers and her initial encounter with the punks takes up the first thirty pages of the book. His detailed descriptions of young people gathered on the sidewalk, Marcia’s thoughts as she walks through these crowds and the impending twilight serve to stretch out the events in his downtempo narrative. His lyrical prose and vivid elements of a night on the streets of Flores kept me earnestly turning the pages in this first part of The Proof:

Aira’s novella has three distinct parts to it, all of which display his masterful ability to play with time in his narrative. The story begins with a sixteen-year-old girl named Marcia walking down a street in Flores, observing other young people talking, hanging out and listening to music. Marcia, a self-conscious, over-weight, slightly depressed, is shocked yet excited when two punk girls named Mao and Lenin yell out to her, “Wanna fuck.” Aira’s chronicle of Marcia moving through the crowd of teenagers and her initial encounter with the punks takes up the first thirty pages of the book. His detailed descriptions of young people gathered on the sidewalk, Marcia’s thoughts as she walks through these crowds and the impending twilight serve to stretch out the events in his downtempo narrative. His lyrical prose and vivid elements of a night on the streets of Flores kept me earnestly turning the pages in this first part of The Proof:

She came up against floating signs: every step, every swing of her arms met endless responses and allusions…with its sprawling youthful world, arriving in Flores was like raising a mirror to her own history, only slightly further from its original location—not far, easily reachable on an evening walk. It was only logical that time should become denser when she arrived.

Marcia decides that she is afraid of the foul-mouthed and overbearing punk girls, but she is also curious enough to find out more about these strange girls so she agrees to have a conversation with them at a nearby burger joint. Aira slows down the tempo of the story in this second part of the book to the point where I was bored and almost gave up on the book. The three girls attempt to have a ridiculous exchange about what it means to be a punk. According to Marcia this means listening to The Cure, wearing dark clothes and sporting a wild, purple hairstyle. The punks, however, reject any such labels. Aira seems to be making fun of his characters and their ridiculous, and at times cruel, “fuck everyone” attitude. This goes on for what seems like a very long, drawn out thirty five pages; he slows down time to the point of oblivion with a long, slow, nihilist discussion among his characters that goes around in circles:

…despite the strangeness of the two punks, she could make out a shallow depth to them: the vulgarity of two lost girls playing a role. Once the play was over, there would be nothing left, no secret, they would be as boring as a chemistry class…And yet at the same time she could imagine the opposite, even though as yet she didn’t know why: maybe the world, once it has been transformed once, can no longer stop changing.

When the trio finally decides to leave the restaurant, the time in the narrative picks up speed to the point that the book feels like it goes by in an instant. I am glad that I stuck with it until the end. The punks decide that they want to prove their love for Marcia by a violent holdup of a grocery store which scene feels like something out of a big budget, action movie. Explosions, shootings and decapitation are all packed into the last twenty-five pages of the novella. By including so much action and description, to the point of shock and gore, Aira brings his narrative to a quick, unsettling and astonishing end:

That was when Mao appeared in a hole created by the broken glass, revolver in one hand and microphone in the other. She looked calm, self-assured, an imposing figure, in no hurry. Above all in no hurry, because she wasn’t wasting a single moment. Things were happening in a packed continuum which they had perfect control of. It was if there were two distinct times happening simultaneously: the one the two punks were in, doing one thing after another without any pause or waiting, and the other of the spectator-victims, where everything was pauses and waiting.

The final scene solidified for me the story as metaphor for the ridiculous things we sometimes do to prove our love for another person. Mao claims that the depth of her love-at-first-sight for Marcia is worth creating such havoc and chaos. Before robbing the cash registers, Mao shouts an interesting message to her victims in the grocery store: “Remember that everything that happens here, will be a proof of love!” Not all of us rob and set fire to grocery stores to prove our love to another person, but some days the hell we put ourselves through in the name of this complex emotion makes us feel like we have gone to the same extremes as Mao. As I was reading Aira’s final, astounding conclusion to The Proof I was reminded of a few lines of the poem “Asphodel, That Greeny Flower” by William Carlos Williams:

I cannot say

that I have gone to hell

for your love

but often found myself there

in your pursuit.

This is my first contribution to Spanish Literature Month hosted by Stu and Richard. Please visit their blogs to see the list of the great selection of books being reviewed.

Bonifacio Reyes has spent his whole life carrying out the commands that others have bestowed on him. When he is a young man he is coaxed into eloping with Emma Valcárcel

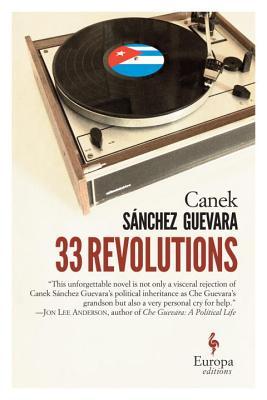

Bonifacio Reyes has spent his whole life carrying out the commands that others have bestowed on him. When he is a young man he is coaxed into eloping with Emma Valcárcel  I first became interested in the tumultuous history of the small island of Cuba when I took a Caribbean politics course in college. It fascinated me that an island which is so geographically close to the United States could be so very different in its political system. 33 Revolutions captures life under the Castro regime from the point-of-view of an ordinary citizen who has become disillusioned from promises of change and is trying to scratch out a bare existence.

I first became interested in the tumultuous history of the small island of Cuba when I took a Caribbean politics course in college. It fascinated me that an island which is so geographically close to the United States could be so very different in its political system. 33 Revolutions captures life under the Castro regime from the point-of-view of an ordinary citizen who has become disillusioned from promises of change and is trying to scratch out a bare existence.

A few times a year I find a book that I rant and rave about and recommend to everyone I know. I become rather obnoxious with my comments that gush with praise. I am giving you fair warning that Two Lines 25 is one of those books. Literature translated from Bulgarian, Chinese, French, German, Hebrew, Japanese, Korean, Norwegian, Russian and Spanish are all contained within the pages of this 192-page volume. I am in awe of the fact that the editors crammed so many fantastic pieces into one slim paperback (there I go gushing again.) This is the type of book that everyone needs to experience for him or herself; but I will attempt to give an overview of some of my favorite pieces.

A few times a year I find a book that I rant and rave about and recommend to everyone I know. I become rather obnoxious with my comments that gush with praise. I am giving you fair warning that Two Lines 25 is one of those books. Literature translated from Bulgarian, Chinese, French, German, Hebrew, Japanese, Korean, Norwegian, Russian and Spanish are all contained within the pages of this 192-page volume. I am in awe of the fact that the editors crammed so many fantastic pieces into one slim paperback (there I go gushing again.) This is the type of book that everyone needs to experience for him or herself; but I will attempt to give an overview of some of my favorite pieces. CJ Evans is the author of A Penance (New Issues Press, 2012), which was a finalist for the Northern California Book Award and The Category of Outcast, selected by Terrance Hayes for the Poetry Society of America’s New American Poets chapbook series. He edited, with Brenda Shaughnessy,

CJ Evans is the author of A Penance (New Issues Press, 2012), which was a finalist for the Northern California Book Award and The Category of Outcast, selected by Terrance Hayes for the Poetry Society of America’s New American Poets chapbook series. He edited, with Brenda Shaughnessy,  What would you do if the man sitting next to you on a plane flight died during landing? When this story begins, a young Dutch woman and an elderly Spanish man are sitting side by side on a plane flight from Barcelona to Holland. The kind and gentle man begins to tell the woman the story of his life and how he ended up on this plane to visit his eldest son. The Dutch woman nods off for a while and upon waking she discovers that the flight has landed and the nice Spanish gentleman has died.

What would you do if the man sitting next to you on a plane flight died during landing? When this story begins, a young Dutch woman and an elderly Spanish man are sitting side by side on a plane flight from Barcelona to Holland. The kind and gentle man begins to tell the woman the story of his life and how he ended up on this plane to visit his eldest son. The Dutch woman nods off for a while and upon waking she discovers that the flight has landed and the nice Spanish gentleman has died. Laia

Laia