I got a true sense of the horror and brutality perpetrated by the Pinochet regime in Chile in a Comparative Politics class in college when I was assigned to read Jacobo Timerman’s book Chile: Death in the South. The most frightening and memorable parts of the book are the personal accounts of Chileans who were beaten and tortured under Pinochet’s reign of terror. The details of the horrific tortured described by these victims has stayed in my mind for 25 years. Timerman also reveals the strategies of ordinary Chileans to avoid being murdered, tortured or disappearing without a trace. I had this book in the back of my mind as I started to read Bolaño’s novella about a priest who lives through the overthrow of Allende’s socialist government and Pinocet’s seizure of power and implementation of a ruthless dictatorship.

Bolaño, who was himself imprisoned for a short time during Pinochet’s rule, takes a different approach towards describing, or not describing, the human suffering of totalitarianism. This brief story is told by a priest named Sebastian Urrutia Lacroix who is on his deathbed and no longer wishes to remain silent about what he has witnessed in his life: “One has to be responsible, as I have always said. One has a moral obligation to take responsibility for one’s actions, and that includes one’s words and silences, yes, one’s silences, because silences rise to heaven too….” Father Lacroix enters the seminary as a teenager and, in addition to his duties as a priest, becomes a prominent poet and literary critic in Chile.

Lacroix has access to the most prominent literary figures of the time including Pablo Neruda whom he meets at a weekend house party. The priest tells various stories about literary friends as well as himself. It’s remarkable that Bolaño not only uses a large variety of literary techniques in his narrative but he makes them flow mellifluously in such a short work. There are stories embedded within stories and Lacroix, as he is telling one of his longer tales, goes on for two or three pages in one long, uninterrupted sentence. For example, the priest takes an extensive tour of European churches and cathedrals in order to study the preservation of these buildings. He finds out that the greatest threat to these monuments are pigeons and priests throughout Europe have taken up falconry to deal with this menace:

…Fr. Pietro whistled and waved his arms and the shadow came down from the sky to the bell-tower and landed on the gauntlet protecting that Italian’s left hand, and then there wa no need to explain, for it was clear to me that the dark bird circling over the church of St. Mary of Perpetual Suffering was a falcon and Fr. Pietro had mastered the art of falconry, and that was the method they were using to rid the old church of pigeons, and then, looking down from the heights, I scanned the steps leading to the portico and the brick-paved square beside the magenta-coloured church, and in all that space, as hard as I looked, I could not see a single pigeon…

One of my favorite literary techniques that Bolaño uses is during a discussion between Lacroix and his mentor, a fellow literary critic, named Farewell. The anaphora employed throughout the conversation makes it appear more like a long-form poem then a dialogue. It’s also a good sampling of Bolaño’s erudite writing which alludes to authors ancient and modern:

And I: You have many years left to live, Farewell, And he: What’s the use, what use are books, they’re shadows, nothing but shadows. And I: Like the shadows you have been watching? And Farewell: Quite. And I: There’s a very interesting book by Plato on precisely that subject. And Farewell: Don’t be an idiot. And I: What are those shadows telling you, Farewell, what is it? And Farewell: They are telling me about the multiplicity of readings. And I: Multiple, perhaps, but thoroughly mediocre and miserable.

But what about Pinochet’s horrible regime and the horrors he inflicts on his fellow Chileans? I had expected something more gruesome, a work of fiction that would as detailed and honest as Timberman’s. But Lacroix, as he says in his opening words, has chosen to keep silent and his account of what takes place in Chile continues to be allusive throughout his deathbed remembrance. One has to pay careful attention to the hints he gives, like the mention of curfews throughout Santiago. Lacroix is recruited by Pinochet and his generals to give them a six week course on Marxism. The dictator and his men are kind to the priest and are good students, but he is riddled with guilt as to whether or not he did the right thing. Could he really have refused Pinochet’s request? Lacroix never says what could have happened to him if he refuses. He doesn’t even speculate. And a female author named Maria Canales holds a weekly literary saloon in her home despite curfews. Her writing is terrible and we can only assume that she is somehow connected to the regime in order to be allowed these privileges.

And so during Pinochet’s 14 year rule, Lacriox continues to read, and write poetry and criticism and only alludes to the vile parts of this dictatorship:

…my howling could only be heard by those who were able to scratch the surface of my writings with the nails of their index fingers, and they were not many, but enough for me, and life went on and on and on, like a necklace of rice grains, on each grain of which a landscape had been painted, tiny grains and microscopic landscapes, and I knew that everyone was putting that necklace on and wearing it, but no one had the patience or the strength or the courage to take it off and look at it closely and decipher each landscape grain by grain…

And what does this deathbed recognition of his continued silence in the midst of totalitarianism accomplish? Few details are given—no torture, rape, accounts of families disappearing in the middle of the night— but he only remarks that the “faces flash before my eyes at a vertiginous speed, the faces I admired, those I loved, hated, envied and despised. The face I protected, those I attacked, the face I hardened myself against and those I sought in vain.”

His concluding words do not sound like those of a man who has confessed his sins and is contrite: “And then the storm of shit begins.”

In an essay entitled “And of My Cuba, What?” author Guillermo Cabrera Infante describes his escape from his island homeland and the Castro regime as “kissing Circe and living to tell it.” He was born in Gibara, Cuba’s former Oriente Province in 1929 and moved with his parents to the capital city when he was twelve-years old. Cabrera Infante’s parents were founding members of Cuba’s communist party and the author himself, as a socialist, opposed the Batista regime and supported the Revolution of 1959.

In an essay entitled “And of My Cuba, What?” author Guillermo Cabrera Infante describes his escape from his island homeland and the Castro regime as “kissing Circe and living to tell it.” He was born in Gibara, Cuba’s former Oriente Province in 1929 and moved with his parents to the capital city when he was twelve-years old. Cabrera Infante’s parents were founding members of Cuba’s communist party and the author himself, as a socialist, opposed the Batista regime and supported the Revolution of 1959. in 1965 trying to escape from Cuba. I highly recommend this fascinating book which portrays his harrowing escape to Madrid and eventually to London where he spends the rest of his life. After his voluntary exile from Cuba, he becomes a staunch and frequent critic of Castro and his government. His essay “And of My Cuba, What?”, written in exile in January of 1992, and “Answers and Questions,” written in July of 1986, are both included in his collected volume of non-fiction writing entitled Mea Cuba translated into English by Kenneth Hall and published in 1994 by Farrar, Strauss & Giroux. Cabrera Infante’s essays are consumed with the nostalgia and longing that one would expect from an exile, a man that never expects to see his birthplace, his family or his friends again. I chose to write about “And of My Cuba, What?” and “Answers and Questions” because they are two of the angriest, most chilling pieces in the collection and have an important message about corruption and greed in government and leadership.

in 1965 trying to escape from Cuba. I highly recommend this fascinating book which portrays his harrowing escape to Madrid and eventually to London where he spends the rest of his life. After his voluntary exile from Cuba, he becomes a staunch and frequent critic of Castro and his government. His essay “And of My Cuba, What?”, written in exile in January of 1992, and “Answers and Questions,” written in July of 1986, are both included in his collected volume of non-fiction writing entitled Mea Cuba translated into English by Kenneth Hall and published in 1994 by Farrar, Strauss & Giroux. Cabrera Infante’s essays are consumed with the nostalgia and longing that one would expect from an exile, a man that never expects to see his birthplace, his family or his friends again. I chose to write about “And of My Cuba, What?” and “Answers and Questions” because they are two of the angriest, most chilling pieces in the collection and have an important message about corruption and greed in government and leadership.

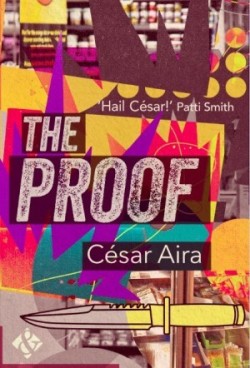

Aira’s novella has three distinct parts to it, all of which display his masterful ability to play with time in his narrative. The story begins with a sixteen-year-old girl named Marcia walking down a street in Flores, observing other young people talking, hanging out and listening to music. Marcia, a self-conscious, over-weight, slightly depressed, is shocked yet excited when two punk girls named Mao and Lenin yell out to her, “Wanna fuck.” Aira’s chronicle of Marcia moving through the crowd of teenagers and her initial encounter with the punks takes up the first thirty pages of the book. His detailed descriptions of young people gathered on the sidewalk, Marcia’s thoughts as she walks through these crowds and the impending twilight serve to stretch out the events in his downtempo narrative. His lyrical prose and vivid elements of a night on the streets of Flores kept me earnestly turning the pages in this first part of The Proof:

Aira’s novella has three distinct parts to it, all of which display his masterful ability to play with time in his narrative. The story begins with a sixteen-year-old girl named Marcia walking down a street in Flores, observing other young people talking, hanging out and listening to music. Marcia, a self-conscious, over-weight, slightly depressed, is shocked yet excited when two punk girls named Mao and Lenin yell out to her, “Wanna fuck.” Aira’s chronicle of Marcia moving through the crowd of teenagers and her initial encounter with the punks takes up the first thirty pages of the book. His detailed descriptions of young people gathered on the sidewalk, Marcia’s thoughts as she walks through these crowds and the impending twilight serve to stretch out the events in his downtempo narrative. His lyrical prose and vivid elements of a night on the streets of Flores kept me earnestly turning the pages in this first part of The Proof: Bonifacio Reyes has spent his whole life carrying out the commands that others have bestowed on him. When he is a young man he is coaxed into eloping with Emma Valcárcel

Bonifacio Reyes has spent his whole life carrying out the commands that others have bestowed on him. When he is a young man he is coaxed into eloping with Emma Valcárcel  I first became interested in the tumultuous history of the small island of Cuba when I took a Caribbean politics course in college. It fascinated me that an island which is so geographically close to the United States could be so very different in its political system. 33 Revolutions captures life under the Castro regime from the point-of-view of an ordinary citizen who has become disillusioned from promises of change and is trying to scratch out a bare existence.

I first became interested in the tumultuous history of the small island of Cuba when I took a Caribbean politics course in college. It fascinated me that an island which is so geographically close to the United States could be so very different in its political system. 33 Revolutions captures life under the Castro regime from the point-of-view of an ordinary citizen who has become disillusioned from promises of change and is trying to scratch out a bare existence.