Robert Hass has been another American poet that I’ve discovered from literary Twitter. My favorite poem in his collection Time and Materials is entitled “The World as Will and Representation.” In this longer poem, which is typical of the longer ones in the book, Hass tells a very personal story. He is thinking back to when he was a ten-year-old boy and his family’s morning routine during which time his father would give his mother a drug called antabuse which was supposed to prevent her from drinking. “It was the late nineteen-forties, a time,/A Social world, in which the men got up/And went to work, leaving the women with the children.” The boy’s father would ground the medication very fine into a powder and put it in his mother’s glass of water was so that she couldn’t spit the pills out. The poet lingers on the vivid details of crushing the pills, handing her the glass and watching her drink.

Robert Hass has been another American poet that I’ve discovered from literary Twitter. My favorite poem in his collection Time and Materials is entitled “The World as Will and Representation.” In this longer poem, which is typical of the longer ones in the book, Hass tells a very personal story. He is thinking back to when he was a ten-year-old boy and his family’s morning routine during which time his father would give his mother a drug called antabuse which was supposed to prevent her from drinking. “It was the late nineteen-forties, a time,/A Social world, in which the men got up/And went to work, leaving the women with the children.” The boy’s father would ground the medication very fine into a powder and put it in his mother’s glass of water was so that she couldn’t spit the pills out. The poet lingers on the vivid details of crushing the pills, handing her the glass and watching her drink.

The ending is incredibly powerful. The boy’s father leaves for work and the child is left alone with his mother:

“Keep and eye on Mama, pardner.”

You know the passage in the Aeneid? The man

Who leaves the burning city with his father

On his shoulders, holding his young son’s hand,

Means to do well among the flaming arras

And the falling columns while the blind prophet,

Arms upraised, howls from the inner chamber,

“Great Troy is fallen. Great Troy is no more.”

Slumped in a bathrobe, penitent and biddable,

My mother at the kitchen table gagged and drank,

Drank and gagged. We get our first moral idea

About the world—about justice and power,

Gender and the order of things—from somewhere.

The passage to which Robert Hass is referring occurs in Vergil’s Aeneid Book II when Aeneas is telling the story of how he escaped Troy with his father and son. Aeneas’s father, Anchises, is paralyzed so he must carry him on his shoulders and hold his young son, Iulus, by the hand. But, but, Aeneas also has a wife, Creusa (2.705-710 translation is my own):

I will carry you on my shoulders, your weight will not burden me.

As things happend around us, we will either be in danger together

or we will both reach safety. And let little Iulus walk beside me

and my wife follow behind.

After Aeneas successfully convinces his father to escape Troy, he tells the rest of the family servants to meet him outside the city at a Temple to Ceres. Aeneas also hands his household gods to his father for safekeeping. Aeneas then sums up their escape (II.721-725, translation is my own):

Having spoken these things, I covered my broad shoulders

with the pelt of a golden lion and lowered my neck

for the impending burden. Little Iulus took hold of my

right hand and followed his father by taking large steps;

my wife walks behind.

That last line in the Latin is striking: pone subit coniunx (the wife walks behind). Aeneas, busy with his father and son, loses Creusa as Troy is burning and he never sees her again. She is one of the characters in the Aeneid that is sacrificed because of Aeneas’s future in Italy where he is destined to marry another woman in a political alliance. Creusa, I think, also foreshadows Dido’s tragic fate.

In his poem, Ross describes the details of Aeneas, the Father, taking care of his father and young son, but he doesn’t specifically mention the detail of the hero’s wife. Creusa does linger in the background of Hass’s poem in the figure of the boy’s mother, “penitent and biddable.” Creusa, like the poet’s mother, is also a victim of “justice and power” and “the order of things.” Hass’s poem brings up so many questions: why was the boy’s mother drinking in the first place? What were the other circumstances of the family? And, most importantly, did this woman also, pone subit, walk behind?

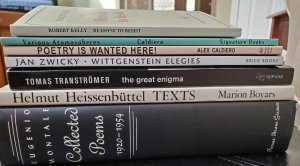

Last night I was reading Robert Kelly’s lovely new poem, Reasons to Resist, which he describes in the subtitle as “a motet.” From the Latin word movere, “to move” a motet is a beautiful, unique style, I thought, for a longer poem which fittingly captures his ideas of music as well as language. The one line I keep repeatedly coming back to is: We all know how to talk/ we just don’t know when.

Last night I was reading Robert Kelly’s lovely new poem, Reasons to Resist, which he describes in the subtitle as “a motet.” From the Latin word movere, “to move” a motet is a beautiful, unique style, I thought, for a longer poem which fittingly captures his ideas of music as well as language. The one line I keep repeatedly coming back to is: We all know how to talk/ we just don’t know when. Yesterday I shared on Twitter a pick up strategy from Ovid that Pound alludes to in the Cantos. I’ve had a request to translate a few more. Here are some of my favorites:

Yesterday I shared on Twitter a pick up strategy from Ovid that Pound alludes to in the Cantos. I’ve had a request to translate a few more. Here are some of my favorites: I have been voraciously reading an incredible amount of excellent poetry lately. I’ve been sharing some of my favorite passages on Twitter, but I thought I would do a short series on the blog of my favorite collections. Frank Bidart’s Half-Light, Collected Poems, which includes work spanning the years 1965-2016 was recommended to me by two of my favorite literary Twitter accounts. It is one of those few collections of poetry that one can read from cover to cover in a few sittings. I devoured it over the course of this past week. My favorite parts of this volume are his series of poems based on Catullus 85 as well as his longer, Hour of the Night, series of poems.

I have been voraciously reading an incredible amount of excellent poetry lately. I’ve been sharing some of my favorite passages on Twitter, but I thought I would do a short series on the blog of my favorite collections. Frank Bidart’s Half-Light, Collected Poems, which includes work spanning the years 1965-2016 was recommended to me by two of my favorite literary Twitter accounts. It is one of those few collections of poetry that one can read from cover to cover in a few sittings. I devoured it over the course of this past week. My favorite parts of this volume are his series of poems based on Catullus 85 as well as his longer, Hour of the Night, series of poems.