Bakkhai continues to be one of Euripides’s (c. 484-406 b.c.e.) most popular plays to stage, translate, and interpret, even though it was never performed in its author’s lifetime. The ancient Greek playwright and Athenian wrote Bakkhai in the last few years of his life in Macedonia, where he had fled after becoming disillusioned with his native city-state. The play was found among his papers after his death and produced posthumously by either his nephew or his son at the Dionysia, the festival held annually for the eponymous god in Athens. The drama presents the god Dionysos arriving in Thebes disguised as a mortal to establish his cult in that city and exact a brutal punishment on his cousin, King Pentheus, who denies the existence of the god. Anne Carson’s unconventional new translation of Bakkhai is a fitting interpretation of what is arguably Euripides’s most enigmatic tragedy.

Bakkhai continues to be one of Euripides’s (c. 484-406 b.c.e.) most popular plays to stage, translate, and interpret, even though it was never performed in its author’s lifetime. The ancient Greek playwright and Athenian wrote Bakkhai in the last few years of his life in Macedonia, where he had fled after becoming disillusioned with his native city-state. The play was found among his papers after his death and produced posthumously by either his nephew or his son at the Dionysia, the festival held annually for the eponymous god in Athens. The drama presents the god Dionysos arriving in Thebes disguised as a mortal to establish his cult in that city and exact a brutal punishment on his cousin, King Pentheus, who denies the existence of the god. Anne Carson’s unconventional new translation of Bakkhai is a fitting interpretation of what is arguably Euripides’s most enigmatic tragedy.

Dionysos is the first character to appear on stage in the play, and he tells us that he is harboring anger for his maternal family who have denied his immortality. Dionysos is the son of Zeus and a mortal woman, Semele, daughter of the king of Thebes. When Semele is pregnant with Dionysos, she is tricked by Hera into viewing Zeus, undisguised, in all his glory as the mighty god of sky and lightning. At the sight of him she is instantly incinerated and Zeus puts the fetus in his thigh to finish gestating, from which appendage of his father Dionysus is eventually born. In her typical precipitous, staccato phrases that are familiar from her previous translations and original poetry, Caron’s rendition of Bakkhai gives us a succinct version of the myth:

[PROLOGUE]

[enter Dionysos]

Dionysos:

Here I am.

Dionysos.

I am

son of Zeus, born by a lightning bolt out of Semele

—you know the story—

the night Zeus split her open with fire,

In order to come here I changed my form,

put on this suit of human presence.

I want to visit the springs of Dirke,

the river Ismenos.

Look there—I see

the tomb of my mother,

thunderstruck Semele,

and her ruined house still smoking

with the live flame of Zeus.

Richard Seaford’s more traditional rendering of the same lines (1996) is:

Dionysos

I am come, the son of Zeus, to this Theban land, Dionysos, to whom the daughter of Kadmos once gave birth, Semele, midwived by lightning-borne fire. And having changed my form from god to mortal, I am here at the streams of Dirke and the water of Ismenos. I see here by the house the home of my thunderbolt-struck mother and the ruins of the house smouldering with the still-living flame of Zeus, Hera’s immortal outrage against my mother.

Carson’s style and language seems more suited to sustaining the attention of a 21st century audience—her version was staged at the Almeida Theatre in London in 2015 to great praise—trying to quickly grasp the background of this myth. Whereas Seaford’s version is typical of what we have to come expect from a translation of an ancient text into English, Carson’s rendition with her succinct, colloquial, flippant sentences are what readers have come to expect from her translations and poetry. Carson does not alter her style to reflect the very different texts of Aeschylus, Sophocles or Euripides. A sample from her translations of tragedian demonstrates how Carson makes their sentences conform to her own tendency towards candid, unambiguous and humorous language.

In her translation of Aeschylus’s Agamemnon, Klytaimensta’s explanation of her affair with her husband’s cousin is full of Carson’s glib language and sarcasm:

KLYTAIMESTRA:

Gentlemen, citizens of Argos, you,

I am not ashamed to tell you of my

husbandloving ways.

Shyness diminishes with age.

The fact is, life got hard for me when he

was off at Troy.

It’s a terrible thing for a woman to sit alone,

in a house,

listening to rumors and tales of disaster

one after another arriving—

why, had this man sustained as may

wounds as people told me,

he be fuller of holes than a net!

And Carson’s version of Sophokles’s Elektra when the title character laments the murder of her father at the hands of her mother her words are plainly spoken and we get a brusque version of the background story:

ELEKTRA:

How many times can a heart break?

Oh Father,

it was not killer Ares

who opened his arms

in some foreign land

to welcome you.

But my own mother and her lover

Aigisthos:

those two good woodsmen

took an axe and split you down like an oak.

And Carson’s version of Aphrodite’s entrance in her translation of Euripides’s Hippolytus is strikingly similar to Dionysos’s first words in The Bakkhai:

APHRODITE:

You know who I am. You know my naked power.

I am called Aphrodite! Here and in heaven.

All who dwell between the Black Sea and the Atlantic,

Seeing the light of the sun—

All who bow to my power—I treat with respect.

Some might criticize Carson for not reflecting the distinct differences in the grammar, syntax, tone, and diction of these ancient authors. But when audience members attend a staging of an Ancient play translated by Carson, they are expecting a version of these Greek texts that are unique because of their reflection of Carson’s own thoroughly modern style.

Although in Ancient Greece Dionysos was a complex god with a long history—he was one of the earliest gods to be mentioned by name in writing as far back as the Bronze Age—Euripides’s play is the only extant tragedy that confronts the dynamic and frightening nature of this deity. Dionysos is usually said to be the god of wine and intoxicated ecstasy, but this is an oversimplification of his divinity. He is also the patron god of Athenian music and drama, a fertility god represented by the phallus, and a god who comforts the dying by freeing them from fear of death. In art and literature he is sometimes depicted as an effeminate young man, but he is more commonly portrayed like the other male Olympian gods, with a beard, and only stands out because he is holding his thyrsos—a stalk of fennel with a pinecone on the end.

While the Greek word theos is commonly used to describe the appearance of a god in person, in this play it is fitting that Euripides often refers to Dionysus as a daimon, a much more nebulous word to define or translate. Walter Burkert in his book Greek Religion discusses this elusive Ancient Greek word:

The gods, theoi, are many-shaped and beyond number, but the term theos alone is insufficient to comprehend the Stronger Ones. From Homer onwards, it is accompanied by another word which has had an astonishing career and lives on in the European languages of the present day: daimon, the demon, the demonic being.

In Carson’s translation of the play she chooses not to translate the word and simply leaves it in her text as daimon. Dionysos himself explains:

I am something supernatural-

Not exactly god, ghost, spirit, angel, principle or element-

There is no term for it in English.

In Greek they say daimon–

Can we just use that?

Whenever the word appears in Carson’s translation, it is left untraslated—it stays as daimon (always italicized.) It would have been enlightening and helpful for a note, or a brief afterword for those who are unfamiliar with the complexity of this word. A piece Carson wrote for the Cahier series entitled Nay Rather helps to explain her choice not to translate daimon. Carson argues in this essay that a type of “metaphysical silence” occurs when it is impossible to translate a word directly from one language to another: “Metaphysical silence happens inside words themselves. And its intentions are harder to define. Every translator knows the point where one language cannot be rendered into another.” Rather than regarding this silence as an obstacle, she uses it to her advantage in The Bakkhai; by leaving it untranslated, the furtive nature of a multifaceted god is heightened within her text.

The descriptions of Dionysos’s mysterious and multilayered workings as a deity continue in the choruses of The Bakkhai, where the strength of Carson’s translation lies. When the Bakkhai, the female followers of Dionysos for whom the play is named, first appear on stage, they describe their patron:

O Thebes! garland yourself

in all the green there is—

ivy green

olive green

fennel green

growing green

yearning green,

we sap green

new grape green

green of youth and green of branches,

green of mint and green of marsh grass

green of tea leaves oak and pine,

green washed needles and early rain,

green of weeds and green of oceans,

green of bottles, ferns and apples,

green of dawn-soaked dew and slender green of roots

green fresh out of pools,

green slipped under fools,

green of the green fuse,

green of the honeyed muse,

green of the rough caress of ritual,

green undaunted by reason or delirium,

green of jealous joy,

green of the secret holy violence of the thyrsus,

green of the sacred iridescence of the dance—

and let all the land of Thebes dance!

with Dionysos leading,

to the mountains!

to the mountains!

The brevity of the language and very curt lines, combined with her loose translation of the Ancient Greek, gives us a text that is both expanded and compressed at the same time. The result is a poetic work of art that stands on its own outside the context of this play.

As the action of the tragedy moves forward, Dionysos, disguised as a mortal and follower of his own cult, argues with Pentheus, the current ruler of Thebes who is also Dionysos’s cousin, about the validity of the god and his cult. Pentheus fails to understand that this disguised stranger is the god himself and repeatedly and ignorantly criticizes the god and his mysteries:

Pentheus:

So are we the first place you’ve brought your new daimon?

Dionysos:

Oh no, people are dancing for Dionysos pretty much everywhere else.

Pentheus:

Foreigners all lack sense, compared to Greeks.

Dionysos:

Well, there’s more than one kind of sense. It’s true they enjoy different customs.

Pentheus:

Are your mysteries performed at night or in the day?

Dionysos:

Mostly at night. Darkness is serious.

Pentheus:

Yes it is, seriously corrupting, for women.

Dionysos:

Can’t corruption be found in daylight too?

Pentheus:

Oh stop being clever! There’s a penalty for that!

Dionysos:

Stop being superficial. You slight the god.

Pentheus:

I can’t believe your arrogance, you casuistical Bakkhic little show off.

Two interesting characters that also make an appearance in the play and whose presence lends to the mystery of its interpretation are the seer Tiresias and Pentheus’s grandfather, Kadmos. These old men enter, dressed in women’s clothing, so that they can go to the mountain and join with the Bakkhai in the worship of Dionysos. They attempt to set an example for Pentheus, but even these elders of the city-state cannot convince him to respect the god:

Teiresias:

You at the gates!

Call Kadmos out—go on, tell him Teiresias is here,

he’ll know why.

We have an agreement, one old man with another,

to try out this Dionysian business together—

fawnskin, thyrsos, garlands in the hair—the complete regalia.

[enter kadmos from palace]

Kadmos:

I knew it was you, my old wise friend,

I heard your voice.

Look, I’ve got my gear on too—the costume of the god!

Now the important thing is

To promote Dionysos

Every way we can,

He’s my daughter’s son after all.

So where are we headed?

I’m ready to dance or trance or toss our white heads,

Or whatever comes next.

You lead the way, Teiresias, you’re the wise one.

I’m merely enthusiastic!

Isn’t it fun to forget our old age?

Teiresias:

Yes well, what is it they say,

You’re as young as you feel?

Kadmos:

We must get to the mountain.

Should we call a cab?

Teiresias:

That doesn’t sound very Dionysian.

Kadmos:

Good point. Let’s walk. We can lean on each other.

As is evident from these two examples, the tone of Carson’s translations of the dialogue alternates between serious and cheeky, the traditional and the colloquial 21st-century idioms. This scene, with two old men appearing on stage in drag, naturally has an element of humor to it, but Carson exaggerates this humor, especially in her absurd line “Should we call a cab?” It lends the scene a dash of the unexpected element—appropriate for a play about a bewildering god; yet the extreme humor seems out of place for a play that ends with a horrible decapitation.

In her essay entitled “Tragedy: A Curious Art Form” Ann Carson writes: “Why does tragedy exist? Because you are full of rage. Why are you full of rage? Because you are full of grief. Ask a headhunter why he cuts off human heads. He’ll say that rage impels him and rage is born of grief.” The Bakkhai ends not with a figurative display of such rage but with a literal cutting off of a human head. Pentheus is convinced by Dionsyos to dress up as a woman and spy on the Bakkhai in the mountains, which plan the king is excited to carry out. When he arrives at the mountain he is viciously attacked, and the woman who tears his head from his shoulders turns out to be his own mother, Agave, whom the god forced into his female cult. In the end, Pentheus gets his comeuppance and Dionysos firmly establishes his rites in Thebes: the god’s rage is born of his grief and is manifests itself in the decapitation of the king.

Although in its most basic sense this play is one of divine punishment, scholars have debated for decades about what moral lesson or message Euripides intended to convey in his tragedy. The fact that Euripides himself was critical of the traditional Greek gods adds to the problems of interpretation. Is Pentheus’s punishment deserved or is Dionysos unnecessarily harsh and vengeful? Theories have ranged widely, from a claim that the drama mirrors a deathbed conversion of a poet who had previously rejected the pantheon of gods to an assertion that it is a commentary on religious fanaticism. Carson’s translation adds another interesting dimension and interpretation to the long history of this play; the colloquial language and humor, I suspect, work well in a dramatic performance of the play. But for those who want a more literal rending of Euripides text it might be better to stick with earlier versions.

[bio]

Time and Space are the focus of Berger’s brief yet lovely writings in this impossible-to-classify book. Part one, entitled “Once” is an attempt to capture the enigmatic, human experience of time while part two, entitled “Here” explores the concept of space especially in relation to sight and distance. The text feels like a series of snapshots into Berger’s mind as he uses art, photography, philosophy, poetry and personal anecdotes to grapple with time and space; Hegel, Marx, Dante, Camus, Caravaggio are just a few of the artists and thinkers that are given fleeting attention in his text.

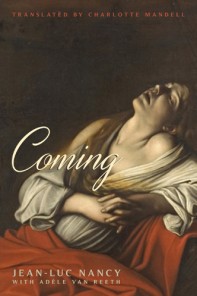

Time and Space are the focus of Berger’s brief yet lovely writings in this impossible-to-classify book. Part one, entitled “Once” is an attempt to capture the enigmatic, human experience of time while part two, entitled “Here” explores the concept of space especially in relation to sight and distance. The text feels like a series of snapshots into Berger’s mind as he uses art, photography, philosophy, poetry and personal anecdotes to grapple with time and space; Hegel, Marx, Dante, Camus, Caravaggio are just a few of the artists and thinkers that are given fleeting attention in his text. Caravaggio’s

Caravaggio’s

The following is an introduction to a review that I have contributed to the latest edition of The Scofield. The theme of this issue is Kobo Abe & Home; the link to the issue that includes my full review is below:

The following is an introduction to a review that I have contributed to the latest edition of The Scofield. The theme of this issue is Kobo Abe & Home; the link to the issue that includes my full review is below: