Pain, and grief and heartsickness can be so lonely and isolating. The rollercoaster of emotions settle down, but there are still days when the pain, the memories of what has been lost feels like a harsh punch in the chest. Who can I talk to? Who can I call? To whom can I describe this almost unbearable sensation? It’s nothing new. It’s more of the same. It makes me weary and I feel like a broken record repeating these tiresome things to those in my inner circle. I’m sick of myself, I think, so how can they not be sick of me too?

Writing and reading poetry are what I end up retreating into when the loneliness and isolation set in. I like to think that all of the books of poetry I have voraciously consumed in the last few years are paying off in the form of solace. I share here two recent favorites that have helped me in the hopes that they might be comforting to anyone suffering in any way—there seems to be an abundance of pain everywhere one looks nowadays.

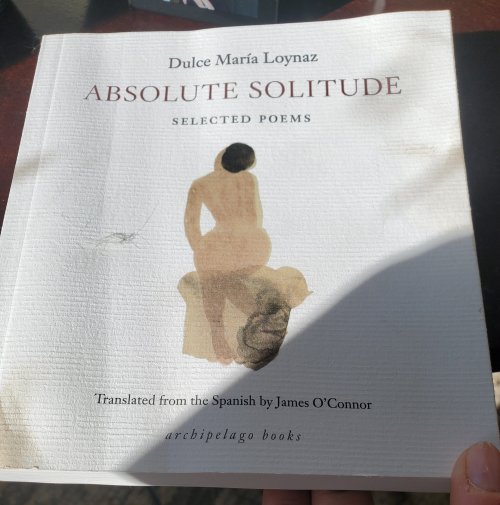

Cuban poet Dulce Maria Loynaz’s collection Absolute Solitude, beautifully translated by James O’Connor and published by Archipelago Books, is full of memorable lines that are worthy of writing in my notebooks and revisiting for those tough days. Here she envisions grief as a wolf to which she falls prey:

There was a lull in the pain. I fled from it as if I were fleeing a wolf suddenly taken with sleep. But when it wakes, it will pick up my scent and follow my trail. I know this. And it doesn’t matter where I hide, it will know how to find me, and when it does, it will pounce on a body too weary to resist it. Why must I be the preyed upon? Why does its mouth water every time it spots me? I have no blood to slake its savage thirst and I carry nothing in my saddlebags but the echoes of dreams grown cold. Where did I lose my way? I can’t remember. What flowers did I step on pretending I didn’t see them? Before me the great jungle grows dense.

And from Kathryn Smith’s Collection Self-Portrait with Cephalopod published by Milkweed Editions a poem that envisions the possibility of being whole again after tragedy. “A Permeable Membrane in the Mutable Cosmos”:

Tell me again of the lepers who learn to shed their disastrous skin by eating the meat of vipers: something transmutable in the flesh. The ancients spent lifetimes considering the resurrection of irretrievable parts: wolf-devoured flank, eyes of martyrs pecked clean in the village square, Tell me again about the new heaven and the new earth, when the bear returns an unblemished arm to its faithful socket, when mountains open their mouths to receive conduits and I-beams and engagement diamonds and the fish ladders the rivers will give up with their dams when the earth is made new. Tell me the formula for feeling whole again after tragedy. The equation for how much time I needed after saying no before I’d tell you yes. Tell me I’ll never be alone, even when I want to be alone.

home today, feeling under the weather, while listening to the weather—pouring rain and loud, booming thunder from the remnants of a hurricane—-I reached for some poetry on my shelves. The selections from Ugly Duckling Presse never disappoint. From their “Lost Literature Series”, Defense of the Idol, first published in 1934, is the only collection ever written by Chilean poet Omar Caceres (1904-1943). Due to typos in the original printing, he tried to burn every copy of his only book. It is translated for the first time in English by Monica de la Torre.

home today, feeling under the weather, while listening to the weather—pouring rain and loud, booming thunder from the remnants of a hurricane—-I reached for some poetry on my shelves. The selections from Ugly Duckling Presse never disappoint. From their “Lost Literature Series”, Defense of the Idol, first published in 1934, is the only collection ever written by Chilean poet Omar Caceres (1904-1943). Due to typos in the original printing, he tried to burn every copy of his only book. It is translated for the first time in English by Monica de la Torre. In an essay entitled “And of My Cuba, What?” author Guillermo Cabrera Infante describes his escape from his island homeland and the Castro regime as “kissing Circe and living to tell it.” He was born in Gibara, Cuba’s former Oriente Province in 1929 and moved with his parents to the capital city when he was twelve-years old. Cabrera Infante’s parents were founding members of Cuba’s communist party and the author himself, as a socialist, opposed the Batista regime and supported the Revolution of 1959.

In an essay entitled “And of My Cuba, What?” author Guillermo Cabrera Infante describes his escape from his island homeland and the Castro regime as “kissing Circe and living to tell it.” He was born in Gibara, Cuba’s former Oriente Province in 1929 and moved with his parents to the capital city when he was twelve-years old. Cabrera Infante’s parents were founding members of Cuba’s communist party and the author himself, as a socialist, opposed the Batista regime and supported the Revolution of 1959. in 1965 trying to escape from Cuba. I highly recommend this fascinating book which portrays his harrowing escape to Madrid and eventually to London where he spends the rest of his life. After his voluntary exile from Cuba, he becomes a staunch and frequent critic of Castro and his government. His essay “And of My Cuba, What?”, written in exile in January of 1992, and “Answers and Questions,” written in July of 1986, are both included in his collected volume of non-fiction writing entitled Mea Cuba translated into English by Kenneth Hall and published in 1994 by Farrar, Strauss & Giroux. Cabrera Infante’s essays are consumed with the nostalgia and longing that one would expect from an exile, a man that never expects to see his birthplace, his family or his friends again. I chose to write about “And of My Cuba, What?” and “Answers and Questions” because they are two of the angriest, most chilling pieces in the collection and have an important message about corruption and greed in government and leadership.

in 1965 trying to escape from Cuba. I highly recommend this fascinating book which portrays his harrowing escape to Madrid and eventually to London where he spends the rest of his life. After his voluntary exile from Cuba, he becomes a staunch and frequent critic of Castro and his government. His essay “And of My Cuba, What?”, written in exile in January of 1992, and “Answers and Questions,” written in July of 1986, are both included in his collected volume of non-fiction writing entitled Mea Cuba translated into English by Kenneth Hall and published in 1994 by Farrar, Strauss & Giroux. Cabrera Infante’s essays are consumed with the nostalgia and longing that one would expect from an exile, a man that never expects to see his birthplace, his family or his friends again. I chose to write about “And of My Cuba, What?” and “Answers and Questions” because they are two of the angriest, most chilling pieces in the collection and have an important message about corruption and greed in government and leadership.