“Our love, tell me, what is it?” Claudine asks this heavy, direct, honest, complex question in a letter to her husband. She is on a short trip to see her daughter, who was conceived during a brief affair with a dentist, at boarding school but is snowed in at her lodgings. There are so many layers to the philosophical language of Musil’s stream-of-conscious narrative; but the one that stood out to me the most was his reflection on love, and how we experience another person through the self and internalize emotions that are created through this experience.

“Our love, tell me, what is it?” Claudine asks this heavy, direct, honest, complex question in a letter to her husband. She is on a short trip to see her daughter, who was conceived during a brief affair with a dentist, at boarding school but is snowed in at her lodgings. There are so many layers to the philosophical language of Musil’s stream-of-conscious narrative; but the one that stood out to me the most was his reflection on love, and how we experience another person through the self and internalize emotions that are created through this experience.

Musil explores the fact that Love is such a complex human emotion, one that can oftentimes be confused or mixed with pity, nostalgia or physical desire. The opening scene in the book depicts Claudine and her husband as quietly content and presumably in love—enjoying a cup of tea, discussing a book, relaxing in their home. But on her journey, as she leaves her husband behind and encounters another man on her trip she reflects on this love that, up until now it seems, she has not questioned. The translation of such a complex text could not have been easy; Genese Grill’s rendering of Musil was wonderful to contemplate and absorb:

So, they drove on, close to each other, in the deepening dusk. And her thoughts began to take on that softly forward-urging restlessness again. She tried to convince herself that it was just a delusion brought on by the confusing interior stillness of this suddenly lonely amid strangers; and sometimes she believed that it was just the wind, in whose stiff, glowing coldness she was wrapped, which made her frozen and submissive; but other times it seemed to her that her husband, strangely, was very close to her again, and that this weakness and sensuality was nothing more than a wonderfully blissful manifestation of their love.

As she is drawn closer to a man on her journey simply known as the “commissioner” these thoughts of her husband and her love for him as well as her life before her marriage keep flashing through her mind.

She felt that she could never again belong to a strange man. And precisely there, precisely simultaneous with this revulsion towards other men, with this mysterious yearning for only one, she felt—as if on a second, deeper level—a prostration, a dizziness, perhaps a presentiment of human uncertainty, perhaps she was afraid of herself; perhaps it was only an elusive, meaningless, diffuse desire that the other man would come, and her anxiety flowed through her, hot and cold, spurning on a destructive desire.

And when she is alone at night:

And then it came to her suddenly, from out of that time—the way that this terrible defenselessness of her existence, hiding behind the drams, far off, ungraspable, merely imaginary, was not living a second life—a calling, a shimmer of nostalgia, a never-before-felt softness, a sensation of I, that—stripped bare by the terrifying irredeemable fact of her fate, naked, disrobed, divested of herself—longed, drunkenly, for increasingly—debased debilitation. She got lost in it, strangely confused by its aimless tenderness, but this fragment of love that sought its own completion.

Claudine’s thoughts are blurred to the point that I felt they could equally apply to her relationship with her husband, her love affairs before her marriage, or her current situation with the commissioner. This fragment of love that sought its own completion. This last sentence, in particular, has given me much to think about.

I found Claudine’s response jarring when the commissioner asks her if she loves her husband: “The absurdity in this prodding, his assumption of certainty, did not escape her, and she said, “No; no, I don’t love him at all,” with trembling and resolution.” She obviously has some love for her husband, so why tell this lie? The hint to this, I think, comes a few pages later:

And then the cryptic thought struck her: somewhere among all these people there was one, one who was not quite right for her, but who was different; she could have made herself fit with him and would never have know anything about the person she was today. For feelings only live in a long chain of other feelings, holding on to each other, and it is just a matter of whether one link of life arranges itself—without any gap in between—-next to another, and there of hundreds of ways this can happen. And then for the first time since falling in love, the thought shot through her: it is chance; it becomes real through some chance or other and then one holds fast to it.

I felt as though Claudine came to the realization that the “completion” (or “perfection” in other translations) of love is never possible. She never sends that letter I quoted to her husband. She has to learn for herself that if love is not returned—in word, in action, in gesture—it will die out. Sometimes it suffers a long, painful death. But, unless it is tended to and nurtured, it will indeed die out.

Adua, written by the Somali, Italian author Igiaba Scego and translated by Jamie Richards, moves among three different time periods and two different settings. The main character, Adua, emigrates from Somalia to Italy and her own story is a mix of her current, unhappy life and flashbacks to her childhood in Somalia. The third thread in the book deals with the protagonist’s father and his time spent as a servant for a rich Italian who is part of the Italian attempt at colonialism in East Africa just before World War II. My issue with the book is that I wanted more details about Adua and her father but the plot was too brief to provide the depth of plot and characterization that I craved. The author could have easily turned this story into three large volumes about Adua’s childhood, her father, and her adult life as an immigrant in Italy. Adua did prompt me to research and learn more about Italian colonialism in the 20th century but other than that I didn’t have strong feelings about the title after I finished it.

Adua, written by the Somali, Italian author Igiaba Scego and translated by Jamie Richards, moves among three different time periods and two different settings. The main character, Adua, emigrates from Somalia to Italy and her own story is a mix of her current, unhappy life and flashbacks to her childhood in Somalia. The third thread in the book deals with the protagonist’s father and his time spent as a servant for a rich Italian who is part of the Italian attempt at colonialism in East Africa just before World War II. My issue with the book is that I wanted more details about Adua and her father but the plot was too brief to provide the depth of plot and characterization that I craved. The author could have easily turned this story into three large volumes about Adua’s childhood, her father, and her adult life as an immigrant in Italy. Adua did prompt me to research and learn more about Italian colonialism in the 20th century but other than that I didn’t have strong feelings about the title after I finished it. Late Fame, written by Arthur Schnitzler and translated by Alexander Starritt, involves an episode in the life of an older man named Eduard Saxberger who is suddenly reminded of a collection of poetry entitled Wanderings that he had written thirty years earlier and has long forgotten. A group of Viennese aspiring writers stumble upon Saxberger’s volume in a second hand bookshop and invite him to join their literary discussions at a local café. Saxberger, although he never married or had a family, considers his life as a civil servant very successful. The young poets, whom Schnitzler satirizes as bombastic and overly self-important, stage an evening of poetry readings and drama at which event Saxberger is invited to participate. Saxberger learns that although it is nice to get a little bit of late fame and recognition from this ridiculous group of writers, he made the correct decision in pursuring a different career. Trevor at Mookse and The Gripes has written a much better review of this book than I could have done and I highly encourage everyone to read his thoughts:

Late Fame, written by Arthur Schnitzler and translated by Alexander Starritt, involves an episode in the life of an older man named Eduard Saxberger who is suddenly reminded of a collection of poetry entitled Wanderings that he had written thirty years earlier and has long forgotten. A group of Viennese aspiring writers stumble upon Saxberger’s volume in a second hand bookshop and invite him to join their literary discussions at a local café. Saxberger, although he never married or had a family, considers his life as a civil servant very successful. The young poets, whom Schnitzler satirizes as bombastic and overly self-important, stage an evening of poetry readings and drama at which event Saxberger is invited to participate. Saxberger learns that although it is nice to get a little bit of late fame and recognition from this ridiculous group of writers, he made the correct decision in pursuring a different career. Trevor at Mookse and The Gripes has written a much better review of this book than I could have done and I highly encourage everyone to read his thoughts:  Party Going by Henry Green describes exactly what the title suggests: a group of British upper class men and women are attempting to get to a house party in France but are stuck at the train station in London because of thick fog. Green’s narrative starts out on a rather humorous note as he describes these ridiculously fussy, British youth. They panic with what Green calls “train fever” every time they think they are in danger of missing their train. They fret over their clothes, their accessories, their luggage, their tea and their baths. As the story progresses they become increasingly mean and petty towards one another which made me especially uncomfortable. The men are portrayed as idiots and dolts who are easily manipulated by the vain and churlish women. In the end I found Green’s characters so unpleasant that I couldn’t write an entire post about them. I’ve read and written some words about his novels Back and Blindness both of which I thoroughly enjoyed. I still intend to read all of the reissues of his books from the NYRB Classics selections even though I wasn’t thrilled with Party Going.

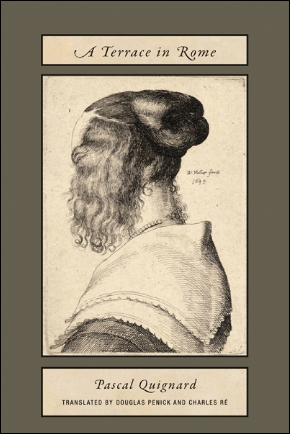

Party Going by Henry Green describes exactly what the title suggests: a group of British upper class men and women are attempting to get to a house party in France but are stuck at the train station in London because of thick fog. Green’s narrative starts out on a rather humorous note as he describes these ridiculously fussy, British youth. They panic with what Green calls “train fever” every time they think they are in danger of missing their train. They fret over their clothes, their accessories, their luggage, their tea and their baths. As the story progresses they become increasingly mean and petty towards one another which made me especially uncomfortable. The men are portrayed as idiots and dolts who are easily manipulated by the vain and churlish women. In the end I found Green’s characters so unpleasant that I couldn’t write an entire post about them. I’ve read and written some words about his novels Back and Blindness both of which I thoroughly enjoyed. I still intend to read all of the reissues of his books from the NYRB Classics selections even though I wasn’t thrilled with Party Going. To read any work by Pascal Quignard whether fiction or non-fiction, is to experience philosophical and literary reflections on sex, love, shadows, art and death. A Terrace in Rome, his novella which won the Grand Prix du Roman de l’Académie Française prize in 2000, explores all of his most favored themes and images via the fictional story of Geoffroy Meaume, a 17th century engraving artist whose illicit love for a woman causes him horrible disfiguration, pain and suffering. The year is 1639 when twenty-one-year-old Meaume, serving an apprenticeship as an engraver, first lays his eyes on Nanni, the eighteen year-old blond beauty who is betrothed by her father to another man. For a while Meaume is happily absorbed in this secret affair and playing in umbra voluptatis (in the shadow of desire.)

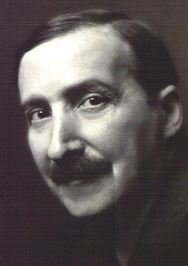

To read any work by Pascal Quignard whether fiction or non-fiction, is to experience philosophical and literary reflections on sex, love, shadows, art and death. A Terrace in Rome, his novella which won the Grand Prix du Roman de l’Académie Française prize in 2000, explores all of his most favored themes and images via the fictional story of Geoffroy Meaume, a 17th century engraving artist whose illicit love for a woman causes him horrible disfiguration, pain and suffering. The year is 1639 when twenty-one-year-old Meaume, serving an apprenticeship as an engraver, first lays his eyes on Nanni, the eighteen year-old blond beauty who is betrothed by her father to another man. For a while Meaume is happily absorbed in this secret affair and playing in umbra voluptatis (in the shadow of desire.) Stefan Zweig is a master at writing short stories that are full of descriptive details, interesting characters and surprise plot twists. It is truly amazing that he manages to do this all within the span of 100 pages. The setting of this short piece is a hotel on the French Riviera where a group of upper class citizens from various countries are vacationing. A shocking social incident has occurred within their social circle and this scandal has all of the guests arguing and gossiping.

Stefan Zweig is a master at writing short stories that are full of descriptive details, interesting characters and surprise plot twists. It is truly amazing that he manages to do this all within the span of 100 pages. The setting of this short piece is a hotel on the French Riviera where a group of upper class citizens from various countries are vacationing. A shocking social incident has occurred within their social circle and this scandal has all of the guests arguing and gossiping.

This psychological thriller starts innocently enough with a kind old woman offering to split a cake with a young woman she meets outside of a bakery in Vienna. But Stift’s novella becomes gruesome, disturbing and haunting very quickly.

This psychological thriller starts innocently enough with a kind old woman offering to split a cake with a young woman she meets outside of a bakery in Vienna. But Stift’s novella becomes gruesome, disturbing and haunting very quickly.

Linda Stift in an Austrian writer. She was born in 1969 and studied Philosophy and German literature. She lives in Vienna. Her first novel, Kingpeng, was published in 2005. She has won numerous awards and was nominated for the prestigious Ingeborg Bachmann Prize in 2009.

Linda Stift in an Austrian writer. She was born in 1969 and studied Philosophy and German literature. She lives in Vienna. Her first novel, Kingpeng, was published in 2005. She has won numerous awards and was nominated for the prestigious Ingeborg Bachmann Prize in 2009.