In the Foreword to the German Library (Volume 44) edition of Gottfried Keller’s stories Max Frisch writes:

In the Foreword to the German Library (Volume 44) edition of Gottfried Keller’s stories Max Frisch writes:

Assuming that the American reader still has this volume in his hands, I would like to point out to him that Gottfried Keller fought for liberalism but was not naïve; he soon grew bitterly apprehensive that middle-class liberalism, the great social achievement of his century, might disintegrate into a profit society pure and simple, without utopias, without transcendent values. And that is what we have today. Or so I fear. If you read further you will find there is something strangely disturbing about these stories: One life after another ends in quiet failure. You won’t notice it immediately because the man who tells these tales has a sense of humor. He likes people even though he sees through them. He is kind. He knows a lot about the relationship between money and morals, for example, and he doesn’t cover it up; because he still has hope.

He would be horrified at his country—as he would be at other “democracies” as well.

Frisch’s words about Keller ring true even more so today than when he wrote them in 1982. Keller’s novellas in the first part of this volume are set in an imaginary place that he calls Seldwyla, a small town where everyone knows each other and gossip is rampant. The men he depicts are hard working but because of their stubbornness and narrow views of the world they bring about their own downfall.

In “The Three Righteous Combmakers,” Jobst, Fridolin and Dietrich are all craftsmen who work for a Seldwylan combmaker. The craftsmen in Seldwyla are usually itinerant, never working for one employer for very long. But these three men refuse to leave their present employer and they all start saving money and pinching pennies to the extreme in order to eventually buy the combmaking business. Gottfried deals with the ridiculous frugality of these men with his typical humor. The men are too cheap, for instance, to even think about taking a wife because of what it would cost them: “He was not accustomed to think of marriage, because he could conceive of a wife only as a person who wanted something from him that he did not owe her…” One day, however, Zus, the daughter of a local laundress, captures the attention of all three men when they learn she is in possession of a small inheritance. They argue, fight, and make fools of themselves to win her hand in marriage; their uncompromising adherence to their plans to get Zus’s money causes the “quiet failure” of all three men.

In the story entitled “A Village Romeo and Juliet,” the farmers that Keller depicts from Seldwyla are equally as stubborn and uncompromising as the combmakers. Marti and Manz are diligent men whose farms are prosperous because of their work ethic. But when a land dispute arises between the men, their focus on this petty issue causes them to neglect their farms and their families. Both men end up penniless and are forced to give up their once productive and beautiful farms. In addition their children, Sali and Verena, fall in love but understand the impossibility of any marriage because of the disapproval of their fathers. What makes Keller’s story different from the typical star crossed lovers tale is that Sali and Verena willingly and even enthusiastically take their own lives in order to control their own fate.

What I appreciated most about Keller’s writing in “A Village Romeo and Juliet” was his detailed descriptions of nature and the Seldwylan countryside. Like the landscape, the feelings that the lovers have for each other are beautiful, raw and natural. When the couple meets for the first time, Keller sets the scene:

Sali went directly out to the quiet, beautiful hillside over which the two fields extended. The magnificent, quiet July sun, the passing white clouds floating above the ripe, waving grain, the blue shimmering fiver flowing below—all this filled him once more, for the first time in years, with happiness and contentment instead of pain, and he stretched out full length in the transparent half-shade of the grain, on the border of Marti’s desolate field, and gazed blissfully towards heaven.

And when the lovers unite in that same field, their words are passionate and genuine, making their ending that much more tragic: “‘Oh Verena,’ he exclaimed, gazing into her eyes with candor and devotion, ‘I’ve never looked at a girl; I’ve always felt that I must love you some day, and without my wishing it or realizing it, you’ve always been in my mind.'”

Keller himself had an interesting life and his writings all have some kind of an autobiographical element. He said, “I have never produced anything which did not have its impetus in my outer and inner life.” Even though was a rather short man, he was quick-tempered and got into a lot of fist fights over the course of his life. He was also quick to fall in love and preferred young, tall and beautiful women. But he was never able to find that one special woman with whom to settle down and marry; every time he got close something got in the way (one of his brides-to-be committed suicide, for instance). His tendency towards fist fights, his unfilled love life , and his struggles with money are all carefully and meticulously reflected in these humorous yet tragic stories.

This collection from The German Library includes ten of Keller’s novellas. A very worthwhile literary purchase. What else is everyone reading this year for German Literature Month?

I have to admit that as a classicist I try to avoid retellings of ancients myths and texts because they never live up to the brilliance of the original authors. I had passed over Wolf’s Medea and Cassandra for this very reason, but a fellow bibliophile with similar reading tastes to my own convinced me to give Wolf’s books a try and I am so glad that I did.

I have to admit that as a classicist I try to avoid retellings of ancients myths and texts because they never live up to the brilliance of the original authors. I had passed over Wolf’s Medea and Cassandra for this very reason, but a fellow bibliophile with similar reading tastes to my own convinced me to give Wolf’s books a try and I am so glad that I did. As a

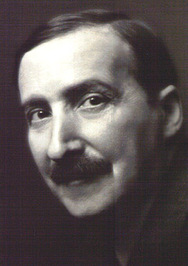

As a  Stefan Zweig is a master at writing short stories that are full of descriptive details, interesting characters and surprise plot twists. It is truly amazing that he manages to do this all within the span of 100 pages. The setting of this short piece is a hotel on the French Riviera where a group of upper class citizens from various countries are vacationing. A shocking social incident has occurred within their social circle and this scandal has all of the guests arguing and gossiping.

Stefan Zweig is a master at writing short stories that are full of descriptive details, interesting characters and surprise plot twists. It is truly amazing that he manages to do this all within the span of 100 pages. The setting of this short piece is a hotel on the French Riviera where a group of upper class citizens from various countries are vacationing. A shocking social incident has occurred within their social circle and this scandal has all of the guests arguing and gossiping.

This is one of those classic books that is very difficult to review and do it justice because there are so many ideas contained within the book. It is a coming-of-age story, a commentary on existential philosophy and a beautiful description of a life long friendship. Narcissus is a teacher’s assistant in the cloister of Mariabronn and fully intends to take his vows as a monk. Narcissus is a very talented scholar and it is evident that he will one day serve the church and even become the Abbot of the cloister. He is a cerebral man who values the intellect but his emphasis on the rational also prevents him from having any real friendships or meaningful love in his life. But this all changes when a young boy by the name of Goldmund is dropped off at the cloister by his father.

This is one of those classic books that is very difficult to review and do it justice because there are so many ideas contained within the book. It is a coming-of-age story, a commentary on existential philosophy and a beautiful description of a life long friendship. Narcissus is a teacher’s assistant in the cloister of Mariabronn and fully intends to take his vows as a monk. Narcissus is a very talented scholar and it is evident that he will one day serve the church and even become the Abbot of the cloister. He is a cerebral man who values the intellect but his emphasis on the rational also prevents him from having any real friendships or meaningful love in his life. But this all changes when a young boy by the name of Goldmund is dropped off at the cloister by his father.

Hermann Hesse was a German-Swiss poet, novelist, and painter. In 1946, he received the Nobel Prize in Literature. His best known works include Steppenwolf, Siddhartha, and The Glass Bead Game (also known as Magister Ludi) which explore an individual’s search for spirituality outside society.

Hermann Hesse was a German-Swiss poet, novelist, and painter. In 1946, he received the Nobel Prize in Literature. His best known works include Steppenwolf, Siddhartha, and The Glass Bead Game (also known as Magister Ludi) which explore an individual’s search for spirituality outside society.