I received a review copy of this title from Pushkin Press via Netgalley. This novella was published in the original German in 1925 and this English version has been translated by Anthea Bell.

My Review:

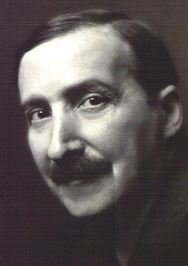

Stefan Zweig is a master at writing short stories that are full of descriptive details, interesting characters and surprise plot twists. It is truly amazing that he manages to do this all within the span of 100 pages. The setting of this short piece is a hotel on the French Riviera where a group of upper class citizens from various countries are vacationing. A shocking social incident has occurred within their social circle and this scandal has all of the guests arguing and gossiping.

Stefan Zweig is a master at writing short stories that are full of descriptive details, interesting characters and surprise plot twists. It is truly amazing that he manages to do this all within the span of 100 pages. The setting of this short piece is a hotel on the French Riviera where a group of upper class citizens from various countries are vacationing. A shocking social incident has occurred within their social circle and this scandal has all of the guests arguing and gossiping.

The narrator, who never gives us his name, is staying on the Riveria and interacts with the other guests, incluing a German husband and wife, a “portly” Dane, an Italian married couple, and a distinguished and older English lady. This group of strangers usually just engage in small talk and mild jokes while eating their meals, but the disappearance of Madame Henriette has disturbed their peaceful routine. A young, handsome and garrulous Frenchman arrived at the hotel on the previous day and captivated everyone’s attention. Zweig shows his skill at describing characters with just the right mix of adjectives and metaphors:

Indeed everything about him was soft, endearing, charming, but without any artifice or affectation. At a distance he might at first remind you slightly of those pink wax dummies to be seen adopting dandified poses in the window displays of large fashion stores, walking-stick in hand and representing the ideal of male beauty, but closer inspection dispelled any impression of foppishness, for—most unusually—his charm was natural and innate, and seemed an inseparable part of him.

The shock comes when Madame Henriette, the wife of a wealthy businessman, disappears with the Frenchman after knowing him for only a couple of days. All of the guests at the hotel are very quick to condemn and judge Henriette for throwing away her marriage, her children and her reputation. The narrator is the only person who comes to Henriette’s defense and reminds the guests that it might have been possible that Henriette was caught in a “tedious, disappointing marriage” and thus had a valid reason for running off with a young man who was virtually a stranger. This heated debate has a profound effect on Mrs. C, the distinguished English lady, who requests a private meeting with the narrator.

The story that Mrs. C. tells the narrator involves an incident in her life when she was forty-two, some twenty years earlier. The incident had left her so embarrassed and mortified that she never told a word of it to another soul, until now. Henriette’s impulsive decision to run away with the Frenchman has brought up old memories for Mrs. C. and she wants to unburden her soul from the guilt of her own folly. Mrs. C. tells the narrator that, as a widow who lost her husband to an unexpected illness, she traveled around Europe while grieving for her beloved spouse. Alone and miserable, she finds herself in Monte Carlo, one of her husband’s favorite places for entertainment, and meets a twenty-four-year old man with a serious gambling problem.

The events that unfold between Mrs. C. and the gambler bring up feelings of passion, anger, redemption, impulsivity and regret. I don’t want to give away what happens between the widow and the young man, but I will say that Zweig has a gift for writing shocking and unexpected plot turns. I never would have guessed the ending to Mrs. C’s story and I was riveted until the very last page of this short book. Zweig shows us that he is an astute observer of human emotions; love, loneliness, passion and sexual desire can make us lose our minds and do irrational things which are completely out of character.

One final aspect of Zweig’s writing that must be mentioned is his careful attention to detail, even in a short work like this novella. When Mrs. C. arrives at the casino, she describes the chiromancy—guessing a person’s moves by observing their hands— that her husband had taught her. This English woman spent hours observing the players’ hands which are much more telling than facial expression. Zweig writes about Mrs. C’s practice of chiromancy:

All those pale, moving, waiting hands around the green table, all emerging from the ever-different caverns of the players’ sleeves, each a beast of prey ready to leap, each varying in shape and colour, some bare, others laden with rings and clinking bracelets, some hairy like wild beasts, some damp and writhing like eels, but all of them tense, vibrating with a vast impatience.

Zweig’s description of the players via their hands is absolutely fascinating and absorbing and is another surprising gem found within the pages of this short piece.

November is German Lit. Month hosted by Lizzy’s Literary Life and Beauty is a Sleeping Cat. The full list of reviews for this event can be found here: http://germanlitmonth.blogspot.co.uk/ and on Twitter #GermanLitMonth.

About the Author:

Zweig studied in Austria, France, and Germany before settling in Salzburg in 1913. In 1934, driven into exile by the Nazis, he emigrated to England and then, in 1940, to Brazil by way of New York. Finding only growing loneliness and disillusionment in their new surroundings, he and his second wife committed suicide.

Zweig’s interest in psychology and the teachings of Sigmund Freud led to his most characteristic work, the subtle portrayal of character. Zweig’s essays include studies of Honoré de Balzac, Charles Dickens, and Fyodor Dostoyevsky (Drei Meister, 1920; Three Masters) and of Friedrich Hlderlin, Heinrich von Kleist, and Friedrich Nietzsche (Der Kampf mit dem Dmon, 1925; Master Builders). He achieved popularity with Sternstunden der Menschheit (1928; The Tide of Fortune), five historical portraits in miniature. He wrote full-scale, intuitive rather than objective, biographies of the French statesman Joseph Fouché (1929), Mary Stuart (1935), and others. His stories include those in Verwirrung der Gefhle (1925; Conflicts). He also wrote a psychological novel, Ungeduld des Herzens (1938; Beware of Pity), and translated works of Charles Baudelaire, Paul Verlaine, and mile Verhaeren.

Most recently, his works provided inspiration for the 2014 film ‘The Grand Budapest Hotel’

This psychological thriller starts innocently enough with a kind old woman offering to split a cake with a young woman she meets outside of a bakery in Vienna. But Stift’s novella becomes gruesome, disturbing and haunting very quickly.

This psychological thriller starts innocently enough with a kind old woman offering to split a cake with a young woman she meets outside of a bakery in Vienna. But Stift’s novella becomes gruesome, disturbing and haunting very quickly.

Linda Stift in an Austrian writer. She was born in 1969 and studied Philosophy and German literature. She lives in Vienna. Her first novel, Kingpeng, was published in 2005. She has won numerous awards and was nominated for the prestigious Ingeborg Bachmann Prize in 2009.

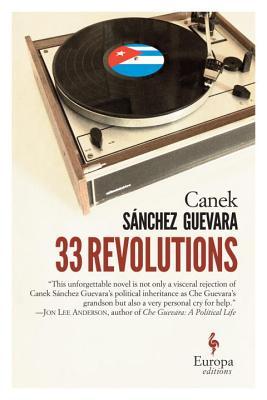

Linda Stift in an Austrian writer. She was born in 1969 and studied Philosophy and German literature. She lives in Vienna. Her first novel, Kingpeng, was published in 2005. She has won numerous awards and was nominated for the prestigious Ingeborg Bachmann Prize in 2009. I first became interested in the tumultuous history of the small island of Cuba when I took a Caribbean politics course in college. It fascinated me that an island which is so geographically close to the United States could be so very different in its political system. 33 Revolutions captures life under the Castro regime from the point-of-view of an ordinary citizen who has become disillusioned from promises of change and is trying to scratch out a bare existence.

I first became interested in the tumultuous history of the small island of Cuba when I took a Caribbean politics course in college. It fascinated me that an island which is so geographically close to the United States could be so very different in its political system. 33 Revolutions captures life under the Castro regime from the point-of-view of an ordinary citizen who has become disillusioned from promises of change and is trying to scratch out a bare existence.

We are first introduced to Andres Egger in 1933 when he has had an unexplained instinct to pay a visit to his elderly neighbor, Horned Hannes. Hannes is a reclusive goatherd who lives in the same Austrian mountain village as Egger and when Egger finds the old man he is barely alive. Egger attempts to carry the goatherd on his back down the mountain but in a fit of madness due to his fever the goatherd runs off into the snow never to be seen again. Between the time that Egger loses the goatherd while carrying him down the mountain and the goatherd’s petrified body is found forty years later on a mountain ledge, we are told the story of Egger’s whole life.

We are first introduced to Andres Egger in 1933 when he has had an unexplained instinct to pay a visit to his elderly neighbor, Horned Hannes. Hannes is a reclusive goatherd who lives in the same Austrian mountain village as Egger and when Egger finds the old man he is barely alive. Egger attempts to carry the goatherd on his back down the mountain but in a fit of madness due to his fever the goatherd runs off into the snow never to be seen again. Between the time that Egger loses the goatherd while carrying him down the mountain and the goatherd’s petrified body is found forty years later on a mountain ledge, we are told the story of Egger’s whole life. Robert Seethaler was born in Vienna in 1966 and is the author of four previous novels. He also works as an actor, most recently in Paolo Sorrentino’s Youth. He lives in Berlin.

Robert Seethaler was born in Vienna in 1966 and is the author of four previous novels. He also works as an actor, most recently in Paolo Sorrentino’s Youth. He lives in Berlin. Karma, comeuppance, what comes around goes around. There are many terms and phrases for the universal of idea of cause and affect. The Brother is a fast-paced, hard-hitting, short book that uses the plot structure of a western as an allegory for demonstrating the balance of good and evil in the world. The author himself has described the book as “a spaghetti western told in poetic prose, simultaneously paying tribute to both Clint Eastwood and Alessandro Baricco.” The plot of this book is a clever structure for the philosophical and existential ideas that the author explores. When a mysterious man, simply known as Brother, arrives in the unnamed town it is a dark and stormy day and the weather reflects the turmoil that three shady and crooked men have caused for the townspeople.

Karma, comeuppance, what comes around goes around. There are many terms and phrases for the universal of idea of cause and affect. The Brother is a fast-paced, hard-hitting, short book that uses the plot structure of a western as an allegory for demonstrating the balance of good and evil in the world. The author himself has described the book as “a spaghetti western told in poetic prose, simultaneously paying tribute to both Clint Eastwood and Alessandro Baricco.” The plot of this book is a clever structure for the philosophical and existential ideas that the author explores. When a mysterious man, simply known as Brother, arrives in the unnamed town it is a dark and stormy day and the weather reflects the turmoil that three shady and crooked men have caused for the townspeople. Rein Raud is the author of four books of poetry, six novels, and several collections of short fiction. He’s also a scholar in Japanese studies and has translated several works of Japanese into Estonian. One of his short pieces appeared in Best European Fiction 2015.

Rein Raud is the author of four books of poetry, six novels, and several collections of short fiction. He’s also a scholar in Japanese studies and has translated several works of Japanese into Estonian. One of his short pieces appeared in Best European Fiction 2015.