Rein Raud was born in Estonia in 1961. Since 1974, he has published numerous poetry collections, short stories, novels, and plays. For his works he has received both the Estonian Cultural Endowment Annual Prize and the Vilde Prize. Having earned his PhD in Literary Theory from the University of Helsinki in 1994, Raud is also a widely published scholar of cultural theory as well as the literature and philosophy of both modern and pre-modern Japan. His book The Brother, translated by Adam Cullen and published by Open Letter in 2016, is a fast-paced, hard-hitting, novella that uses the plot structure of a western as an allegory for demonstrating the balance of good and evil in the world. Raud has described the book as “a spaghetti western told in poetic prose, simultaneously paying tribute to both Clint Eastwood and Alessandro Baricco.” The structure of this book is a clever choice to deal with the philosophical and existential ideas that the author explores.

Raud’s second novel to be translated into English is The Reconstruction, also translated by Adam Cullen and published in April 2017 by Dalkey Archive Press. Enn Padrick, the narrator of The Reconstruction begins writing in a journal in order to catalog his private investigation into his young, adult daughter’s bizarre death. In this book Raud captures the general mood of what I would call a resentful acceptance of Soviet occupation through Enn’s memories of his earlier life: “I was a Pioneer and a member of the Komsomol (the Leninist Young Communits League) and hated the Soviet regime just like everyone else—not especially believing that it would even end, but also not of the opinion that it could be served with integrity.” Soviet rule lingers in the background of Enn’s life and has a great effect on his relationships, especially his marriage and his interactions with his in-laws.

The Death of the Perfect Sentence is Raud’s latest book to be translated into English by Matthew Hyde and published by Vagabond Voices. The novel traces the plot of a group of Estonian youths who have formed an alliance to collect and smuggle secret KGB files out of Estonia. The events in the novel take place just before the collapse of the Soviet Union and Raud provides a rich and multifaceted peek into the lives of everyday Estonians during this transitional time period. I found it especially fascinating that the book allows us to see how different people and different generations dealt with life under Soviet rule. The best writing and most enlightening parts of the book are the ones in which the author inserts his own voice and commentary into the fictional story. Raud describes his life as an Estonian living during and after the occupation, his first trip to Finland, and his motivations for writing this book.

Our interview took place via e-mail over the course of a few weeks during May of 2017. I found Rein to be personable, kind, intelligent and thoughtful. I hope you enjoy reading his answers as much as I have.

Melissa Beck (MB): In addition to being a widely translated and read author, you are also a scholar and an expert in cultural theory as well as the literature and philosophy of pre-modern and modern Japan. Can you give us a professional background and tell us how you came to write fiction and have it translated into English?

Rein Raud (RR): Both of my parents have been free-lance writers as long as I remember, so books and reading have been a part of my world from the very beginning. Most Estonian homes have a big bookshelf, but even in comparison to those we had a huge library, inherited in part from my father’s stepfather, after whom I am named. He was a scholar with very wide interests, even though his fate did not let him realize those very well. He was deported to Siberia after WW II and never regained the position he had had before. But there were his books, including, for example, some works by D.T.Suzuki and Alan Watts, as well as Richard Wilhelm’s translations of Chinese philosophy into German. This is where I first got a taste of East Asian thought. Reading in foreign languages is a part of a proper Estonian education, since far from everything is readily available in our own. Under the Soviet occupation the knowledge of languages was especially important. The main source of reliable information about the world was the Finnish TV for us – the Soviets could not interfere with it, because then people in Helsinki would not have seen it either. The Finns never dubbed any films, so we could hear proper English, German, French and even Japanese or Arabic quite often from the screen. So when I was 10 years old my parents gave me a university textbook of Finnish and told me to learn the language, which I did. (Finnish is very similar to Estonian, the distance is less than between Italian and Spanish.) After that, learning languages became my hobby – I studied Swedish, German, French, Italian, Spanish, Hungarian and a few more, even a bit of Persian and Kiswahili.

With some of these languages I am still more or less comfortable, even though they need a bit of brushing up before going to these countries, some others I have forgotten. So when it was time to decide what I am going to study at the university, I already knew it had to be Asian languages and cultures. But I do not consider myself primarily an Asian Studies scholar, I’d rather like to think that what I have is a proper contemporary education, which is not based on any one single region of the world. And I am happy it lets me earn my keep, as freelance writing is no longer an option.

M.B.: Your three books that have been translated into English are so very different. But one common feature that I have noticed in all of them is your interesting choice of narrative structure and narrative voice, especially in The Death of the Perfect Sentence. Not only does the narrative change between the different characters, but you also insert your own voice into the text with personal experiences. Is there a particular author or books that inspired you to use and experiment with such interesting viewpoints?

R.R.: Estonian critics have also pointed that out and this may indeed be a characteristic of my writing – some authors keep writing the same book all over again, and sometimes very interestingly, but for me a book is done when it is done. Sometimes I want to revisit some topics and some moods, but there has to be something substantially different in the effort. And each story dictates its own way of telling. For The Death of the Perfect Sentence I did not find the proper form for a long time. I had even applied for a scholarship in order to write it and went to a beautiful writer’s home in Italy to work in peace and quiet, but when I had written a few pages I understood that I could not do it yet, I did not have the form. And wrote The Reconstruction instead, another story that had been bothering me for quite some time and was waiting to come out. But then, at a certain point, I realized that what had been missing from The Death of the Perfect Sentence was precisely my own voice. This was not a story that I could write as if standing on the outside. Maybe more than with any other of my novels it was difficult to take leave from it – even after I had written it, I felt its presence. So I also kept rewriting, inserted some new textboxes, left out some previous material and so on.

As to an influence – no, I don’t think there are any strongly present in that book. In some others, such as The Brother, for example, or Hotel Amalfi, which has not been translated, I know my text is the meeting point of several other authors who have been important for me for various reasons: The Brother is a “spaghetti western” conjoining the aesthetics of Sergio Leone and Clint Eastwood with a particularly sensitive way of writing that has haunted me since I first read Alessandro Baricco. Hotel Amalfi, in turn, is in dialogue simultaneously with Richard Brautigan and Gustav Meyrink, the Austrian teller of sombre tales. In both cases I thought that the streams that have come together in my book should in principle be incompatible, but when I later met Alessandro Baricco he told me that he had been just as fascinated by spaghetti western films in his youth.

M.B.: The complicated relationships that evolve between family members are a recurring tension in all of your books: Brother/sister, father/daughter, husband/wife. Did you write with these specific tensions in mind or do they materialize as your plot progresses in the writing process?

R.R.: Family has always been very important to me. I was raised that way and my own family is also like that – both me and my wife are in daily communication with both our children, and as we all work in creative areas, we can provide each other with outsider’s views of what we are doing. My characters have not always been so lucky, that is true. I think sometimes it is the source of people’s problems that they adopt, in regard with each other, the positions social conventions have suggested they should, instead of interacting with each other as the persons they are.

M.B.: All of your books have larger philosophical and existential themes. In the Brother, we are asked to contemplate freedom and what that means for an individual. In Reconstruction the role of religion, personal belief systems and the consequences when they are taken to their extremes is explored. And in The Death of the Perfect Sentence, the concept of trust, especially in Estonia as its citizens are struggling for freedom, is explored in great detail. Why do you think that fiction is the best genre to write about these ideas? Why not just write philosophical treaties or essays?

R.R.: Well, I have written quite a few philosophical texts as well. But academic philosophy is not what philosophy used to be. In one of my earlier novels entitled Hector and Bernard, one of the main characters (himself a professor of philosophy) says that “philosophy” means “love of wisdom” and so “professional philosophers” are “professional lovers of wisdom” and we all know what the expression “professional lovers” means. I do not quite share the scepticism, but it is true that such philosophical debates that could really change your life do not occur very often in academic philosophy, which is more and more about what A said about what B said about what C said. Fiction can thus be the ground where philosophical ideas can re-enter the world, so to say, even if it is only in the form of the stories we can tell about it.

M.B.: Your novel Reconstruction, in particular, deals with the aftermath of Soviet occupation and its impact on Estonian youth. The characters in this book are searching for a place to fit into the world and struggle with existential crises. What would you say has been the lingering effects of the Soviet era on Estonian society as a whole and in Estonian youth in particular?

R.R.: I have been teaching at universitites for the most part of my life now and have thus always had the opportunity to see what young and inquisitive minds are concerned with. And the transition between the intellectually fairly secure world of high school and the unfathomable world of possibilities offered at the university is difficult to many of them. You tell them that the jury is out, has been out for centuries, and most likely will stay out on one question or other, and it bothers them – they want the truth. Answers, not questions. Because if you are being told what the answers are and you then mould your world according to them, you have also escaped the basic responsibility that the fact of your personal freedom has stranded you with. And then it is so much easier later in life to blame anyone – the government, the society, your close ones – for your wrong choices. I have been wondering for years how it is even possible that when our societies become more and more pragmatic and science-based, religious fanaticism and fundamentalism are still on the rise rather than a forgotten thing of the past. I suppose the question is much more relevant for the United States than to Estonia – it is just that for us, the situation arrived in a much more abrupt manner. When the country was occupied and we thought of what it would be like to live in a free and democratic society, we never imagined that human stupidity will have such an important role in forming our environment. School shootings? Never. We just are not this kind of people. Unfortunately, the first school shooting has already occurred in Estonia as well. We haven’t yet had a collective religiously inspired suicide like the one I have described in my book – if it has contributed even a little toward avoiding it, it has done its job.

M.B.: What are the biggest differences you have seen in the type of literature being written by Estonian authors pre-occupation and post-occupation?

R.R.: The best writers whose main work was done during the years of occupation – Jaan Kross, for example, or Arvo Valton, or the many fine poets – contributed a lot toward the formation of a rather sophisticated literary culture. Books could be published in tens of thousands of print runs and were still not very easy to get – and that with a population of about one million. Of course, all published works were carefully censored, and the readers knew that very well. But they, too, had learned to read between the lines. Rich metaphors, subtle irony, abstract and absurd situations or historical narratives that had certain parallels with the present – all these were the only ways to describe the present that could not be touched directly. When the occupation ended, the literary culture changed quickly, as the naked present dominated the writing of many new authors and also the literary institution itself switched to capitalist mode. Books became less affordable especially for those in whose lives they had played a major part. Print runs became smaller, traditional bookstores gave way to new ones or just disappeared. Luckily, we have an institution called the Cultural Endowment, to which certain amount of the taxes on alcohol, tobacco and gambling are directed, and which gives out grants also for publishing houses so that they could publish Estonian literature – on purely economic terms this would not be feasible. So, to a certain extent we have managed to preserve the literary culture and many people still consider reading as one of their favourite ways to spend the time they can have for themselves. But, paradoxically, even though many of the most successful books published now are much easier to read, there are still fewer people who read them.

M.B.: Since you yourself are an expert translator and understand intimately the delicate art of translation, how closely do you work with the translators of your novels? How does this process work? Do conflicts arise and how do you solve them?

R.R.: I have been trying to read the translations of my books into the languages I can read in. With both my English translators I have also had a very good working relationship. Maybe the fact that I have translated myself makes me even better able to respect their choices. After all, what matters is that the end result sounds natural in the language of the translation, not that absolutely everything of what was there in the original gets transmitted at the expense of the clarity and readability (which, after all, were also there in the original). So normally I read the translation and only compare it to the original when something starts to bother me – and usually that is an expression the translator has misunderstood. Of course, some phrases and turns are more important than others, but I think a good translator feels them intuitively.

M.B.: In one of the personal asides in The Death of the Perfect Sentence you discuss the Chinese curse: “May you live in interesting times.” But you turn this into a positive commentary about the fact that living in Estonia during the occupation gave you a great deal of perspective. You state: “So what if this has stirred hungers in me which have damaged me? I am willing to pay that price, if only for the perspective it gave me, which is something I do not encounter in people who have lived under only one political order.” As someone who has only lived in one political system I have to agree with you. Can you elaborate on this?

R.R.: I most certainly hope that you will go on living in the same political system that has ruled in the United States throughout its history. Although the present situation has exposed some of its very significant flaws, it has historically been in the nature of democracy to self-correct and adapt to circumstances, which is something totalitarian systems cannot do. They either stand or fall, which is why in the end they always fall. Unfortunately they may inflict a lot of suffering on the people before that.

I personally believe that it is the capacity of human beings to think and act freely that is ultimately the reason for the greatest achievements of us all. But there is also another side to human nature, an instinct to value stability over risk, a willingness to believe in simple and truthful-sounding answers to complicated questions instead of thinking about them for oneself. It allows certain powers to cajole people into giving up their freedoms and submit to the caring gaze of various Big Brothers for the illusion of safety. I think my own experience makes me very sensitive to such things as ideologically motivated activities that concentrate the power of the state, or extol the alleged pre-eminence of one culture at the expense of others (even if that extolled culture is what I consider my own).

M.B.: In Sergei Lebedev’s book The Year of the Comet, he wrote that the impending fall of the Soviet Union was seen in very subtle ways by its people. For instance, there was a lack of strange things in stores—there were plenty of shoes but no shoelaces. In The Death of the Perfect Sentence you mention experiencing shortages and food rationing before occupation came to an end in Estonia. What other signs pointed to the collapse of communist rule in Estonia?

R.R.: Well, the fate of the regime was decided when the fear it was based upon started to go away. Gorbachev probably had no clue about the extent to which the regime was dependent on the currency of “alternative facts” when he encouraged the people to speak freely about the problems of the society. Its very structure was its basic problem. Even though for many people “freedom” also, or perhaps even primarily, meant the bountiful stores and supermarkets of capitalist economies, the revolt against the system in the Baltics was not an economical one. On the contrary – the was a common saying that we agree to eat potato peel, if only we can be free. But as long as the very basic principles of freedom do not matter to you, you cannot really be free. Even if you live in a free society.

M.B.: There a poignant scene in The Death of the Perfect Sentence in which one of the Estonian young men, Erwin, travels outside of Estonia for the very first time and gets a taste of freedom. I know that you love to travel and visit different countries. Do you remember the first time you traveled outside of Estonia and what that felt like? Did this experience contribute to your love of travel nowadays?

R.R.: Yes – I had a hobby of learning the basics of quite a few foreign languages while still in high school. This allowed me to travel in my mind. The skills have come in quite handy now that I have been able to visit many of these cities I could only imagine in my thoughts, and many more. You may remember how, in The Reconstruction, the narrator tells about having to explain during a French lesson how to get from the Louvre to the church of Notre-Dame, while neither himself nor his teacher believed they would ever be able to visit Paris. This was very much what happened during our English lessons at school.

When my mother, who was born in 1932, was first able to visit Finland somewhere in the late 1970s, she said that the trip felt a bit like returning home after a long stay in a foreign country. Indeed, I suppose Estonia would have looked more or less what Finland looked like, if the occupation had not taken place. For me, it resembled a home I had never visited, but which had existed as an idea throughout my life.

M.B.: I found it interesting that The Death of the Perfect Sentence veers into a romantic plot of sorts between an Estonian woman and a Russian man. For me it served to highlight the tension between these cultures and the occupier versus the occupied. What made you decide to include this romance as part of the plot?

R.R.: There are two such pairs actually: the relationship between Lidia and Raim, even if twisted and poisoned by insincere motivation, is a mirror image of that between Maarja and Alex, the young lovers. I never thought of Alex as the personifier of the occupier – rather, he seems to me as a representative of the Russia that might have been, and that could be briefly glimpsed during some of the Yeltsin years. Alex is a kindred spirit of those thousands of Muscovites who stood up against the coup in 1991 and defended their parliament from the military – and who had never had a problem with the independence of the Baltics or any of the satellite states of the USSR. However, in the relationship between Raim and Lidia, a young and nationalist Estonian man with an apolitical, but kind and decent Russian woman, a bit of the problem is reflected that was to emerge between Estonians and Russian-speaking minority after liberation. Quite a few Russians were not very enthusiastic about the Soviet system either, but a long period of totalitarianism (and not much to remember from before that time) had lured them into a disposition of submissiveness to the powers. After all, they considered the Soviet Union to be their state, which Estonians never did – for us, it was just an evil that had to be lived with, until there was a chance not to. So Lidia does not see working as a typist for the KGB to be a moral problem, but betraying herself and her higher human values is something she is not capable of. For Raim, unfortunately, the opposite is the case – unless we concede that the fight for freedom can be the highest human value that can justify other betrayals. A complicated question, yes, but things are never simple. And this is precisely where the duty of the writer emerges – to speak about the fates of those singular people who were, but should not have been crushed by the wheels of history, even if those wheels are moving in a very desirable direction. It is only later that narratives of history are produced for mass consumption, and I thought it my duty to write against the current narrative of the history of Estonian liberation – not because it would be completely wrong, of course, but because it is too simple.

M.B.: In one of your personal aside in The Death of the Perfect Sentence you write about your Grandad who, among other adventures, trained to become a nurse under tsarism. Do you think will ever write that book? What writing projects are you currently working on? Can we look forward to more of your novels being translated into English?

R.R.: I certainly hope that I will at one point be able to take up The Plague Train – this is the intended title for the book about the humanitarian train that Tsarist Russia sent to Manchuria to vaccinate people and to help to stop the spread of plague there. One of the wagons of that train carried huge amounts of spirits and the nurses, my grandfather among them, who did the vaccinations, were almost constantly drunk – because of fear. My grandfather never spoke about these experiences to my mother (he died before I was born, so I only know all this second-hand), and I can infer something only from one episode – in a station he went to the toilet and saw a corpse there, immediately retreated, but never told anyone else, as then they would have feared that he might be infected and refrain from contact with him. A secluded, even if moving space, with lots of ambitious drunk young men in it, all afraid of their environment, and possibly of each other – a really dramatic situation, if you think of it. So yes, I definitely want to write that one day, but it needs lots of research.

And that book will have to wait, as I have several others on my table. I am just now putting the finishing touches on another long-term project entitled The Clock and the Hammer after an ancient Nordic card game. This is my longest novel yet (longer than The Reconstruction and The Death of the Perfect Sentence put together) and happens mostly in an imagined country manour on the Northern coast of Estonia. We see it in four historical periods: the early 19th century when it was reconstructed by an eccentric Baltic German aristocrat (of whose travels in the world we also learn), in the late 1940s, when an orphanage works in that same building, in the end of the 1970s, when it is a kolkhoz office and is reconstructed so that it could become a cultural centre (as many such manours historically were), and, finally, in 2016, when it is a museum that houses the art collections of the aforementioned aristocrat. Each historical period has its own bit to add to the general narrative. The first pages of this were written down already in 1987, but after that it was always too difficult to write it, because the present was changing so quickly. Other ideas took over in the meantime, and now I am actually very happy I never had the chance to finish the book in such an early period of my life, as it is now quite obviously much more mature than it would have been. Then there is another manuscript, more or less ready, but cooling off for almost a year now, a story that runs in two parallel lines – one in an experimental prison that tries to reform a small group of convicts by teaching them creative writing, and the other dealing with a journalist’s independent murder investigation of a controversial politician. At a certain point, the lines converge. So yes, there will be more novels, and these, too will all differ from each other.

The nine stories in this collection are Stendhal’s translations and retellings of historical records from Italy in the 16th century which depict the upper classes behaving very badly: forbidden love, murder, adultery, torture, poisoning are all found within the pages of Stendhal’s translations. Written between 1829 and 1840, most of the stories in this volume were not published until Stendhal’s death. He tells us himself, in the beginning of “The Duchess of Palliano”, why the stories from this time period and in this part of Europe so fascinated him. Stendhal believes that “Italian passion” is something that no longer exists in the literature and culture of his own era. Love, in particular, he observes, has given rise to so many tragic events among the Italians and Stendhal is fascinated with visiting Italy and searching through the archives of Rome, Florence and Siena to find stories of these “Italian passions”:

The nine stories in this collection are Stendhal’s translations and retellings of historical records from Italy in the 16th century which depict the upper classes behaving very badly: forbidden love, murder, adultery, torture, poisoning are all found within the pages of Stendhal’s translations. Written between 1829 and 1840, most of the stories in this volume were not published until Stendhal’s death. He tells us himself, in the beginning of “The Duchess of Palliano”, why the stories from this time period and in this part of Europe so fascinated him. Stendhal believes that “Italian passion” is something that no longer exists in the literature and culture of his own era. Love, in particular, he observes, has given rise to so many tragic events among the Italians and Stendhal is fascinated with visiting Italy and searching through the archives of Rome, Florence and Siena to find stories of these “Italian passions”:

Nox

Nox

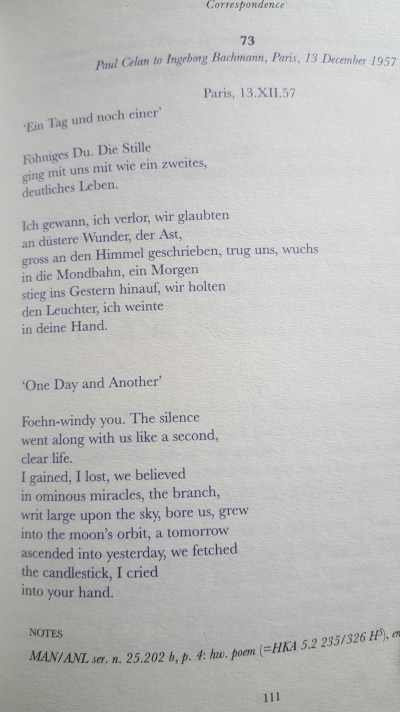

I have always loved handwritten, personal letters; they are so much more tangible, intimate and sensual than the digital correspondence to which we have become accustomed in the 21st century. There is a certain anticipation and excitement when one sends a letter and eagerly waits for a response; to see the other person’s handwriting, to touch the object they once touched, to tuck it away in a special place are all of the things we lose with digital communication. When I was reading the letters, post cards, notes, telegrams and poems sent between Ingeborg Bachmann and Paul Celan I felt like I was eavesdropping or spying on the unfolding of an intense, passionate and, at times tortured, love affair. I wondered what this correspondence would look like in the 21st century and it occurred to me that texts, direct messages, emails and video chats would not have the same underlying tone of intimacy that one feels while reading the Bachmann and Celan letters.

I have always loved handwritten, personal letters; they are so much more tangible, intimate and sensual than the digital correspondence to which we have become accustomed in the 21st century. There is a certain anticipation and excitement when one sends a letter and eagerly waits for a response; to see the other person’s handwriting, to touch the object they once touched, to tuck it away in a special place are all of the things we lose with digital communication. When I was reading the letters, post cards, notes, telegrams and poems sent between Ingeborg Bachmann and Paul Celan I felt like I was eavesdropping or spying on the unfolding of an intense, passionate and, at times tortured, love affair. I wondered what this correspondence would look like in the 21st century and it occurred to me that texts, direct messages, emails and video chats would not have the same underlying tone of intimacy that one feels while reading the Bachmann and Celan letters.