I had the chance to spend some time vacationing in Maine over the Thanksgiving Holiday. Like any truly dedicated bibliophile, I seek out used bookstores wherever I go and Maine has some great selections. I browed a rather large one in Wells which not only has rooms and rooms full of books but also has a rather large selection of maps. I came home with an interesting mix of books, the first of which is a copy of Petronius’s Satyricon. Now why would a classicist need another translation of Petronius’s bawdy novel, you might ask. This copy that I found was published in 1931 and is the translation attributed to Oscar Wilde. It is attributed to Wilde but no one is quite sure if he actually did the translation himself or if he translated it from the original Latin text. There are large parts of the translation that were borrowed from three previous translations. In addition, the original copies of the book were published without naming the translator on the title page but instead the publisher sent out each copy with a slip indicating that the translator was Sebastian Melmoth, Wilde’s pseudonym. For more information on this interesting literary hoax, here is a link to an excerpt of an article that was written about this translation: https://muse.jhu.edu/article/373513/pdf

![]()

The next book I found as I wandered the many rooms of this bookstore was a copy of Thackeray’s Ballads published in 1856. He is, of course, most famous for his longer work Vanity Fair and it was nice to discover that he had written this short volume of Ballads. It’s interesting that this author who was known for his satirical works also wrote love poems and some short narrative poems. The particular bookshop seems to have many editions of very old books. This particular book of Thackeray’s Ballads is not valuable and I only paid $7.50 for it, but it is now one of the oldest books I have on my shelves.

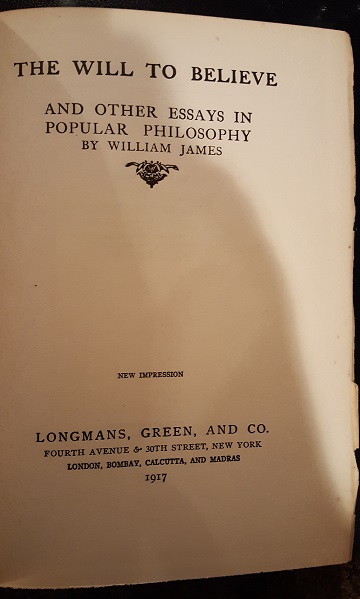

Next, I was specifically looking for a copy of anything I could find by William James, the American pragmatist philosopher. I recently read American Philosophy by John Kaag and his discovery of a long-forgotten library with over 10,000 books, some of which beloved to James, renewed my interest in American philosophy. I was surprised when the bookstore clerk said that books by American philosophers are very popular and I was lucky to find this copy of James’s essays published by Longmans, Green, and Co. in 1917. This collection of essays includes some of his most famous such as “Is Life Worth Living” which was delivered at Harvard’s Holden Chapel in 1985.

The final book that I found is my favorite of the collection. At the entrance to the bookshop there is a huge table with stacks of books on the table and around the table that are the shop’s most recent arrivals that haven’t been categorized yet. I walked up to these piles, which are rather daunting, and plucked a slim volume of poetry off the top. The author of the book is William Dwight Crane and I noticed that there is a handwritten inscription inside the book that reads, “For Angel, From Bill in memory of many happy times. December 19, 1932.” The book is also signed by the author. I researched the author’s name on the Internet and could find no biographical information on him or titles of other books that he wrote. This lonely, slim volume might have been sitting on a pile in that bookshop all but forgotten for years. I am happy to give it a new home with my other books will it will be used and read from time to time.

The poems are a bit simple, but they are clearly from the heart and there is something about their simplicity that captivated me. I will share one such poem entitled “Beauty and Love” from the collection:

Beauty is the soul of man’s desire

A blessed synthesis of pity, joy, and pain

Burned from out the centre of that fire

Of Passion which else were but a stain

Upon our shields, a funeral pyre

On which in each succeeding age have lain

The ashes of the deeds to which men’s hearts aspire,

Only to rise on phoenix-wings to urge men on again,

Beauty of form, and subtle harmony of line,

Beauty of thought and faery fantasy,

Beauty of deed, which makes the thought divine

Compose this substance born of ecstasy,

We need but fashion it with gentile hands,

And, lo! the image Love before us stands.

My daughter, who also inherited the reading gene, found some books to add to her own growing collection, including one about the ocean. True bibliophiles know that used bookstores can be such great places of adventure and discovery. What are your favorite bookshop finds?

One of my favorite things about reading books from small presses are the literary gems that I discover from their quiet and brave authors. Country Life, the latest novel from Ken Edwards, is one such piece of fiction released by Unthank Books. It is not surprising that Edwards is also a poet, has published several volumes of poetry and is also a musician. The text of Country Life oftentimes reads more like a poem or a song than the prose of fiction. This is very fitting for Edwards’s main characters who are musicians that like to do interesting experiments with their craft.

One of my favorite things about reading books from small presses are the literary gems that I discover from their quiet and brave authors. Country Life, the latest novel from Ken Edwards, is one such piece of fiction released by Unthank Books. It is not surprising that Edwards is also a poet, has published several volumes of poetry and is also a musician. The text of Country Life oftentimes reads more like a poem or a song than the prose of fiction. This is very fitting for Edwards’s main characters who are musicians that like to do interesting experiments with their craft. The premise of this Green novel is deceptively simple: Charley Summer, recently released from a POW camp in Germany during World War II, is repatriated back into England. Although Charley suffers from a severed leg for which he must wear a prosthesis, his greatest source of pain is the love that he lost while he was in that German prison camp. Rose, a woman with whom he was having a passionate love affair, dies from an illness before Charley is sent home. We first meet Charley when he is trying to find Rose’s grave in an English churchyard and we immediately discover that the plot is much more complicated than we were first led to believe.

The premise of this Green novel is deceptively simple: Charley Summer, recently released from a POW camp in Germany during World War II, is repatriated back into England. Although Charley suffers from a severed leg for which he must wear a prosthesis, his greatest source of pain is the love that he lost while he was in that German prison camp. Rose, a woman with whom he was having a passionate love affair, dies from an illness before Charley is sent home. We first meet Charley when he is trying to find Rose’s grave in an English churchyard and we immediately discover that the plot is much more complicated than we were first led to believe. Henry Green (1905–1973) was the pen name of Henry Vincent Yorke. Born near Tewkesbury in Gloucestershire, England, he was educated at Eton and Oxford and went on to become the managing director of his family’s engineering business, writing novels in his spare time. His first novel, Blindness (1926), was written while he was at Oxford. He married in 1929 and had one son, and during the Second World War served in the Auxiliary Fire Service. Between 1926 and 1952 he wrote nine novels, Blindness, Living, Party Going, Caught, Loving, Back, Concluding, Nothing, and Doting, and a memoir, Pack My Bag.

Henry Green (1905–1973) was the pen name of Henry Vincent Yorke. Born near Tewkesbury in Gloucestershire, England, he was educated at Eton and Oxford and went on to become the managing director of his family’s engineering business, writing novels in his spare time. His first novel, Blindness (1926), was written while he was at Oxford. He married in 1929 and had one son, and during the Second World War served in the Auxiliary Fire Service. Between 1926 and 1952 he wrote nine novels, Blindness, Living, Party Going, Caught, Loving, Back, Concluding, Nothing, and Doting, and a memoir, Pack My Bag. The title itself intrigued me when I was trying to decide which Rhys book to read for this event. The oxymoron “Good Morning, Midnight” comes from a poem by Emily Dickinson:

The title itself intrigued me when I was trying to decide which Rhys book to read for this event. The oxymoron “Good Morning, Midnight” comes from a poem by Emily Dickinson:

The most important decisions and in our lives can oftentimes be traced to the events of a single day. Jane Fairchild is a writer in her nineties and decided that this would be her career on one preternaturally warm spring day in March of 1924. Jane was a maid at the Beechwoods estate for the Niven family and she was having a secret affair with the upper class son who lived on the neighboring estate and on this day in March her lover summons her to his room for an afternoon of sensual pleasure.

The most important decisions and in our lives can oftentimes be traced to the events of a single day. Jane Fairchild is a writer in her nineties and decided that this would be her career on one preternaturally warm spring day in March of 1924. Jane was a maid at the Beechwoods estate for the Niven family and she was having a secret affair with the upper class son who lived on the neighboring estate and on this day in March her lover summons her to his room for an afternoon of sensual pleasure.