As I was reading Klest’s tragic play, I kept thinking about Ovid’s imagery in Amores IX in which poem he portrays love as warfare. The Latin poet writes:

Militat omnis amans, et habet sua castra Cupido;

Attice, crede mihi, militat onmis amans.

Every lover is a soldier, and Cupid has his own camp;

Atticus, believe me, every lover is a soldier.

Ovid proceeds, in the rest of his poem, to lay out the similarities between soldiers and lovers: both must keep up a constant vigil, pass through companies of guards and be willing to fight against challenging obstacles. Kleist weaves this theme of soldier-as-lover throughout his tragedy, but what is unique to the German writer’s use of this motif is that he applies it to both male and female.

Odysseus and other Greek warriors are the first to appear on stage in the drama. They describe Penthesilea, this strange Amazon warrior, as a crazed woman who can’t settle on an alliance; she fights both Greeks and Trojans alike. As the Greeks approach her to make an attempt at an alliance with her Amazon forces, she sees Achilles and can’t take her eyes off of him. From that moment forward, her greatest desire is to take him as her captive. But, as the customs of her all-female society are gradually revealed in the play, we understand that her motives for overtaking the Greek hero in battle are unusual—warfare for her is a means to achieving love.

Kleist, in an attempt to build classic dramatic suspense, doesn’t give his main characters any dialogue until the fourth scene of the play during which Achilles finally makes an appearance. We have been told by the other characters that Achilles has narrowly escaped being overcome by Penthesilea and he is very angry that a woman almost got the better of him. At this point he has no romantic feelings for this woman, but her attack causes him to go into a rage and he refuses to go back to the Greek camp until he engages her in battle. Kleist’s speech is a brilliant and emotional inversion of Ovid’s image of lover acting as soldier. In Achilles speech it is the soldier whose actions resemble that of a lover:

A man I feel myself and to these women,

Though alone of all the host, I’ll stand my ground.

Whether you all here, under cooling pines

Range round them from afar,

Full of impotent lust,

Shunning the bed of battle in which they sport

All’s one to me; by heav’n you have my blessing,

If you would creep away to Troy again.

What that divine maid wants of me, I know it;

Love’s messengers she sends , wings tipp’d with steel,

That bear me all her wishes through the air

And whisper in my ear with death’s soft voice.

I never yet was coy with any girl.

Warfare is described with terms normally associated with love—the bed of battle, for instance—which not only lends emotion to Achilles’s speech, but also foreshadows what will develop between him and Penthesilea. Later, when he meets her in battle he can’t believe that a woman who can fight with such ferocity and skill exists; it is her prowess as a warrior that causes him to fall in love immediately. When he wounds Penthesilea in their skirmish, he puts aside his weapons and professes his feelings for her. He sees in this fierce woman, a soul that is equally as intense and misunderstood as himself. One of the most shocking declarations Achilles makes in the entire play is to Penthesilea: “Say to her that I love her.” Kleist’s Achilles is just as passionate and emotional as that of Homer’s; what is shocking about this version of Achilles is his declaration of the emotion of love, and for a woman who is not his captive or his prize.

The image of lover-as-soldier and soldier-as-lover also pervade Penthesilea’s speeches and actions. The very reason she is on the battlefield in the first place is to find a man as a partner. She explains the savage founding of her female city where men are not allowed to live or fight. A warlike tribe of Scythians invaded their city, Penthesilea explains, killing all of the men and taking the women as their captives. After suffering horrible abuse, the women fought off their subjugators and banned all men from the city as the women themselves became fierce warriors. The Amazons continue the lineage of their city by conquering men in battle, bringing them back to the Temple of Diana where they mate with the fertile Amazons in what is called the “Feast of the Flowering Virgin.”

Penthesilea by Arturo Michelena, 1891.

The war at Troy with the Greeks was the Amazon’s perfect opportunity for subduing soldiers for the annual mating ritual. Penthesilea doesn’t expect, however, to find such a spectacular hero and mate as Achilles and she is overcome with passion for him to the point of madness. In an even stranger inversion of Ovid’s poem, the female becomes the soldier of love:

Do I not feel—ah! too accursed I—

While all around the Argive army flees,

When I look on this man, on him alone,

That I am smitten, lamed in my inmost being,

Conquered and overcome—I Only I!

Where can this passion which thus tramples me,

harbor in me, who have no breast for love?

Into the battle will I fling myself;

There with his haughty smile he waits me, there

I’ll see him at my feet or no more live!

Once Achilles and Penthesilea finally meet they confess their deeply intense love for one another. But an issue as to where they would reside—among the Amazons or back in Greece—causes a misunderstanding that leads to tragedy. Kleist’s ending for both of these characters varies greatly from that of Homer and the Greek tradition in epic. I usually find it hard to read sources that alter the Greek tradition, but Kleist’s play preserves the spirit of these fierce warriors and lovers, so I was able to get beyond his changes to their story. I will end with a line from Ovid’s Amores that sums up what happens to both of these soldiers/lovers:

quosque neges umquam posse iacere, cadunt

Those whom you would never have thought possible to be brought down, they fall.

As a side note, I read the translation by Humphrey Trevelyan that is included in the German Library’s edition of Kleist’s plays. I found the archaic language and verse distracting at times. I just ordered the translation by Joel Agee and published by Harper which is a prose translation with illustrations. I am very interested in comparing the translations. Has anyone else read either of these?

In an essay entitled “And of My Cuba, What?” author Guillermo Cabrera Infante describes his escape from his island homeland and the Castro regime as “kissing Circe and living to tell it.” He was born in Gibara, Cuba’s former Oriente Province in 1929 and moved with his parents to the capital city when he was twelve-years old. Cabrera Infante’s parents were founding members of Cuba’s communist party and the author himself, as a socialist, opposed the Batista regime and supported the Revolution of 1959.

In an essay entitled “And of My Cuba, What?” author Guillermo Cabrera Infante describes his escape from his island homeland and the Castro regime as “kissing Circe and living to tell it.” He was born in Gibara, Cuba’s former Oriente Province in 1929 and moved with his parents to the capital city when he was twelve-years old. Cabrera Infante’s parents were founding members of Cuba’s communist party and the author himself, as a socialist, opposed the Batista regime and supported the Revolution of 1959. in 1965 trying to escape from Cuba. I highly recommend this fascinating book which portrays his harrowing escape to Madrid and eventually to London where he spends the rest of his life. After his voluntary exile from Cuba, he becomes a staunch and frequent critic of Castro and his government. His essay “And of My Cuba, What?”, written in exile in January of 1992, and “Answers and Questions,” written in July of 1986, are both included in his collected volume of non-fiction writing entitled Mea Cuba translated into English by Kenneth Hall and published in 1994 by Farrar, Strauss & Giroux. Cabrera Infante’s essays are consumed with the nostalgia and longing that one would expect from an exile, a man that never expects to see his birthplace, his family or his friends again. I chose to write about “And of My Cuba, What?” and “Answers and Questions” because they are two of the angriest, most chilling pieces in the collection and have an important message about corruption and greed in government and leadership.

in 1965 trying to escape from Cuba. I highly recommend this fascinating book which portrays his harrowing escape to Madrid and eventually to London where he spends the rest of his life. After his voluntary exile from Cuba, he becomes a staunch and frequent critic of Castro and his government. His essay “And of My Cuba, What?”, written in exile in January of 1992, and “Answers and Questions,” written in July of 1986, are both included in his collected volume of non-fiction writing entitled Mea Cuba translated into English by Kenneth Hall and published in 1994 by Farrar, Strauss & Giroux. Cabrera Infante’s essays are consumed with the nostalgia and longing that one would expect from an exile, a man that never expects to see his birthplace, his family or his friends again. I chose to write about “And of My Cuba, What?” and “Answers and Questions” because they are two of the angriest, most chilling pieces in the collection and have an important message about corruption and greed in government and leadership.

Umberto Saba’s unfinished novella Ernesto, published this year in a new English translation by The New York Review of Books, is part of an ever-growing body of recent literature that explores the idea that human sexuality is more pliable and fluid than the rigid labels to which we assign it. The latest novels by Bae Suah (A Greater Music), Andre Aciman (Enigma Variations), and Anne Garreta (Sphinx and Not One Day) have also opened up important conversations about experimentation with sexuality. But what sets Ernesto apart and makes it stand out among the works of these other authors is that it was written in 1953, a time in which many considered homosexuality scandalous, or often illegal.

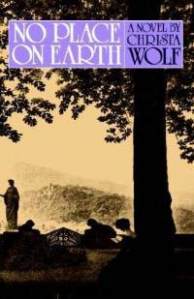

Umberto Saba’s unfinished novella Ernesto, published this year in a new English translation by The New York Review of Books, is part of an ever-growing body of recent literature that explores the idea that human sexuality is more pliable and fluid than the rigid labels to which we assign it. The latest novels by Bae Suah (A Greater Music), Andre Aciman (Enigma Variations), and Anne Garreta (Sphinx and Not One Day) have also opened up important conversations about experimentation with sexuality. But what sets Ernesto apart and makes it stand out among the works of these other authors is that it was written in 1953, a time in which many considered homosexuality scandalous, or often illegal. Christa Wolf stuns us with her literary prowess and creative genius in this novella by imagining two talented, tragic, nineteenth century authors meeting at an afternoon tea. Heinrich von Kleist, who had a military career before embarking on a series of trips throughout Europe, is best known for his dramatic works and novellas. Karoline von Günderrode, who lived in a convent for unmarried, impoverished, aristocratic women, is best known for her poetry and her dramatic works. Both Kleist and Günderrode were unlucky in love, prone to depression and anxiety, and committed suicide at a young age. Through the meeting of these two tragic figures Wolf explores the complications that each gender encounters in relation to social pressures and self-identity.

Christa Wolf stuns us with her literary prowess and creative genius in this novella by imagining two talented, tragic, nineteenth century authors meeting at an afternoon tea. Heinrich von Kleist, who had a military career before embarking on a series of trips throughout Europe, is best known for his dramatic works and novellas. Karoline von Günderrode, who lived in a convent for unmarried, impoverished, aristocratic women, is best known for her poetry and her dramatic works. Both Kleist and Günderrode were unlucky in love, prone to depression and anxiety, and committed suicide at a young age. Through the meeting of these two tragic figures Wolf explores the complications that each gender encounters in relation to social pressures and self-identity. Karoline von Günderrode was born in 1780 to am impoverished, aristocratic, German family. At the age of nineteen she went to live in a convent of sorts, the Cronstetten-Hynspergische Evangelical Sisterhood in Frankfur am Main, which housed poor young woman and widows from upper class families who were waiting for the right man to marry. While at the convent she was determined to educate herself and began writing poetry, drama and letters. She spent time with many of the important intellectuals of her day including Clemens Brentano, Goethe, Karl von Savigny, Bettina von Arnim and Friedrich Creuzer who read her works and gave her feedback. Christoph von Nees published two volumes of her writings under the pseudonym “Tian” in 1804 and 1805. In a letter included in the anthology Bitter Healing: German Women Writers 1700-1830, Günderrode responds to Clemens Brentano who has accused her of sounding rather masculine and “too learned” in her poetry:

Karoline von Günderrode was born in 1780 to am impoverished, aristocratic, German family. At the age of nineteen she went to live in a convent of sorts, the Cronstetten-Hynspergische Evangelical Sisterhood in Frankfur am Main, which housed poor young woman and widows from upper class families who were waiting for the right man to marry. While at the convent she was determined to educate herself and began writing poetry, drama and letters. She spent time with many of the important intellectuals of her day including Clemens Brentano, Goethe, Karl von Savigny, Bettina von Arnim and Friedrich Creuzer who read her works and gave her feedback. Christoph von Nees published two volumes of her writings under the pseudonym “Tian” in 1804 and 1805. In a letter included in the anthology Bitter Healing: German Women Writers 1700-1830, Günderrode responds to Clemens Brentano who has accused her of sounding rather masculine and “too learned” in her poetry: