In 1893-1894 Proust wrote a story for Les plaisirs et les jours entitled “The Indifferent One.” But at the last minute he pulled it and substituted it with a different piece of writing. Burton Pike, whose translation of the story is published in Conjunctions No. 31, says that as Proust was beginning to write A la recherche du temps perdu in 1910 he was looking for a copy of this story. It is a short tale about a man and a woman who, because they feign indifference towards one another—neither will be the one to admit to love first—they lose their chance of being together. It is not known whether he ever found his copy of the story, but Proust’s deeper thoughts on indifference are woven everywhere into the fabric of his magnum opus.

Indifference, which is closely related to memory and time in Proust, is a favorite subject of his within two specific contexts: love and death. In the various stages of the love affairs that he describes, indifference is the alpha and omega, so to speak, of a relationship. It is always used as a strategy or a weapon by one lover to goad the other into returning that love. As Swann is pursing Odette’s affections his modus operandi is described: (tran. Moncrieff et al.) “Thus the simple and regular manifestations of this social organism, the ‘little clan’ automatically provided Swann with a daily rendezvous with Odette, and enabled him to feign indifference to the prospect of seeing her, or even of a desire not to see her; in doing which he incurred no very great risk since, even though he had written to her during the day, he would of necessity see her in the evening and accompany her home.” And the narrator himself, as a young man pining away for Swann’s daughter, Gilberte, uses, or tries to use, the same strategy of faking an indifference towards her. When Gilberte sends Marcel invitations to see her, he starts to decline thinking that this will lure her to him:

“…when she made appointments for me to see her I used often to accept them and then, at the last moment, write to her that I was prevented from coming, but with the same protestations of my disappointment that I should have made to anyone whom I had not wished to see. These expressions of regret, which we keep as a rule for people who do not matter, would do more, I imagined to persuade Gilberte of my indifference than would the tone of indifference which we affect only to those whom we love. When, better than by mere words, by a course of action indefinitely repeated, I should have proved to her that I had no appetite for seeing her, perhaps she would discover once again an appetite for seeing me!”

But Proust does acknowledge that all of this pretending and false lack of emotion is a cruel and cold thing to subject a person to, especially someone we claim to love: “Furthermore, our mistake is our failure to value the intelligence, the kindness of a woman whom we love, however slight they may be. Our mistake is our remaining indifferent to the kindness, the intelligence of others.” He learns this painful lesson in his most important love affair with Albertine.

After the love affairs in Proust come to a long, painful ending, indifference is desperately hoped and wished for by the lover; Proust writes about a mad, jealous, love-sick Swann:

“Examining his complaint with as much scientific detachment as if he had inoculated himself with it in order to study its effects, he told himself that, when he was cured of it, what Odette might or might not do would be a matter of indifference to him. But the truth was that in the depths of his morbid condition he feared death itself no more than such a recovery, which would in fact amount to the death of all that he now was.”

It is only when an irreversible indifference to her sets in that Swann finds any real relief from his sorrows. And Marcel himself, due to his forced separation with Gilberte through feigned indifference and rejecting her invitations, finally experiences true indifference towards her: “I had arrived at a state of almost complete indifference to Gilberte when, two years later, I went with the grandmother to Balbec.” The true test of the end of the affair for Proust is utter and complete indifference.

When the death of his grandmother fully impacts the narrator in his second visit to Balbec he reflects on the indifference the dead have for us and the indifference we eventually develop for those who leave us. He keeps dreaming about his grandmother and is disturbed that, although she seems alive, she treats him with indifference: “But in vain did I take her in my arms, I did not kindle a spark of affection in her eyes, a flush of colour in her cheeks. Absent from herself, she appeared not to love me, not to know me, perhaps not to see me. I could not interpret the secret of her indifference. of her dejection, of her silent displeasure.” And as time goes on and the memories of his grandmother fade, he has deep guilt about the indifference he eventually feels for her as well.

In Time Regained, just at the point in which he becomes indifferent to death, as his health fails and he comes close to death, he begins to worry about the state of his writing and his work. But he realizes that when he is gone, and really even before then, the reception of his novel will be out of his control: “I was surprised at my own indifference to criticism of my work but from the time when my legs had given way when I went downstairs I had become indifferent to everything; I only long for rest until the end came. It was not because I counted on posthumous fame that I was indifferent to the judgments of the eminent today. Those who pronounced on my work after my death could think what they pleased of it.”

Indifference in love and death culminates in the novel with Albertine and his intense, jealousy riddled relationship with her. His cruelest sham of indifference is when Marcel asks Albertine to leave him and he pretends he no longer loves her. It is this false indifference that eventually drives her away from him. But in the case of this love affair, separation, oblivion, indifference is achieved through Albertine’s sudden death. It takes him a year of painful mourning, of making connections with other friends and of travelling for him to finally reach this stage, “As for the third occasion on which I remember that I was conscious of approaching an absolute indifference with respect to Albertine (and on this third occasion I felt that I had entirely arrived at it,) it was one day, at Venice, long after Andree’s visit.”

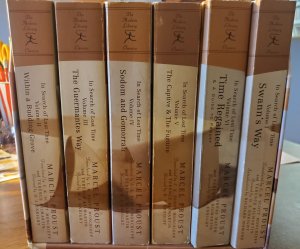

As with most things I’ve read in Proust he has me thinking about and second guessing whether or not we are truly capable of reaching complete indifference towards someone whom we have loved. After all, Swann does marry Odette, Marcel still feels a twinge of jealously years later when he finds out about Gilberte’s other lover, and Albertine’s name appears until the very end of the novel. The word indifferent or indifference appears 23 times in Swann’s Way, 38 times in A Budding Grove, 22 times in The Guermantes Way, 19 times in Sodom and Gomorrah, 48 times in The Captive and The Fugitive, and 41 times in Time Regained. The Moncrieff et al. edition of In Search of Lost Time includes a discussion of Proust’s favorite topics and themes, including memory, time, music, death, etc. It’s a shame that indifference isn’t mentioned as well because he clearly thought about and struggled with this emotion, whether feigned or real.

I had never really thought about this theme before, but you — and Proust — are right about the games we play and how others can be hurt by pretended indifference. And at the same time, feeling the real thing, in the case of indifference to a past relationship, is not easy to do either.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s not easy at all. It seems we can feel true indifference towards someone or something we’ve never cared about.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes… I think it’s the price of feeling deeply.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting and well-observed. From personal experience, I can say that indifference is possible if the ending was somewhat amicable, although hatred is far more common.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes, I was thinking that hatred is the other extreme here. Interesting that there is really an absence of hate in Proust.

LikeLike

What an interesting post. There *is* a think line between love and hate, I think – and playing hard to get doesn’t always work. It does seem like Proust has so much to say about the human condition.

LikeLiked by 1 person

* that’s a thin line, of course….. ;D

LikeLike

I’m not sure if Proust ever even talks about love. He uses the word, but he really always seems to actually be referring to desire, possession, and selfishness. I halfway remember thinking that the Narrator longs for some kind of selfless love but never experiences it, and points in the end to our selfish desires being at the heart of all our unhappiness. The indifference you point out so well here is just another facet of this selfish desire.

One of the nicer ironies of this novel is that had the Narrator actually achieved indifference, he wouldn’t have been able to write the novel; he’d have lost touch with the impressions and memories out of which the whole thing is built. “Time” is memory. Memory is life. What a great book.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think he genuinely hinks he is in love.

LikeLike

But isn’t that the problem with the concept of love? How do we know when it’s truly love? And the answers. differs from one person to the next so greatly. I think that’s the point, his struggles are all our struggles.

LikeLike

Great post!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you.

LikeLike