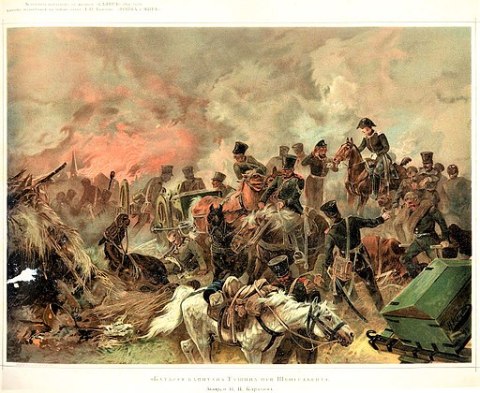

The Battle of Schöngrabern. 1883.

As I am making my way through War and Peace, I can’t help but notice the similarities of theme, narrative techniques and even characters between Tolstoy’s epic and Homer’s Iliad. I was glad to see in Steiner’s essay Tolstoy or Dostoevsky a small section explaining what Steiner feels is Homer’s significant influences on Tolstoy, not just in War and Peace, but in all of his writings, even his autobiographical pieces. Steiner writes:

The Homer of the Iliad and Tolstoy are akin in yet another respect. Their image of reality is anthropomorphic; man is the measure and pivot of experience. Moreover, the atmosphere in which the personages of the Iliad and of Tolstoyan fiction are shown to us is profoundly humanistic and even secular. What matters is the kingdom of this world, here and now.

This concentration of what Steiner calls an anthropomorphic reality is particularly evident in Tolstoy’s descriptions of why upper class men, accustomed to rich and pampered lives, voluntarily go to war and sacrifice their comfort for the Russian monarchy. I have written in a previous post about the Ancient Greek concept of kleos (“glory” or “fame”) which theme Homer weaves throughout his narrative. In Bronze Age Greece kings and wealthy men also leave behind their families and relatively comfortable lives in order to fight at Troy and win kleos. Homer’s Bronze Age warriors, however, want fame not only in this life but also in the next; they will give up their mortal existence in exchange for eternal glory.

Tolstoy’s heroes in War and Peace have motives similar to the warriors in the Iliad. But I would argue that the men who are fighting the French in Tolstoy’s epic have incitements for battle that are more deeply anthropomorphic—of the here and now, as Steiner would say—than the Homeric heroes. Tolstoy spends a great deal of time laying out both Prince Andrei’s and Count Rostov’s reasons for volunteering to fight in the war. In my initial post, I discussed Prince Andrei’s dissatisfaction with his marriage and the boredom he feels while attending insipid society balls and parties. Tolstoy, at first, describes the Prince as a man that wants something more exciting and meaningful in his life but it is not just boredom that is his driving force to step onto the battlefield. We learn that Prince Andrei’s hero is, ironically, Napoleon himself, the very man against whom the Russians are fighting. The Prince craves the recognition, fame and glory that is bestowed on this most famous of French commanders. As an adjutant on General Kutuzov’s staff he prepares for the battle of Austerlitz and daydreams of earning his mark of greatness, no matter the cost:

‘Well then,’ Prince Andrei answered himself, ‘I don’t know what will happen and I don’t want to know, and can’t, but if I want this—want glory, want to be known to men, want to be loved by them, it is not my fault that I want it and want nothing but that and live only for that. Yes, for that alone! I shall never tell anyone, but, oh God! What am I to do if I love nothing but fame and men’s love? Death, wounds, the loss of family—I fear nothing. And precious and dear as many persons are to me—father, sister, wife–those dearest to me—yet dreadful and unnatural as it seems, I would give them all at once for a moment of glory, of triumph over men, of love from men I don’t know and never shall know, for the love of these men here,’ he thought, as he listened to voices in Kutuzov’s courtyard.

These words could just as easily have been spoken by Achilles or Hector in the Iliad.

Count Rostov, at the tender age of eighteen, also volunteers to be a part of the cavalry in the war against the French. Rostov is more naïve and youthful than Prince Andrei, but he too is seeking fame and glory. But there is a major difference between the type of fame that Prince Andrei and Rostov crave. The Prince wants to be know by all men, but Rostov wants to be known by one man, in particular, the Russian Emperor Alexander I. Rostov gets his first glimpse of the Emperor while the army is on parade in front of their beloved leader. Rostov can only be described as smitten at the sight of his sovereign and his sole motivation for fighting in the war is to distinguish himself and gain the notice of Alexander I. The description of Rostov’s love for his Emperor, as the troops prepare for the battle of Austerlitz, is striking:

And Rostov got up and went wandering among the camp fires dreaming of what happiness it would be to die—not in saving the Emperor’s life (he did not even dare to dream of that) but simply to die before his eyes. He really was in love with the Tsar and the glory of the Russian arms and the hope of future triumph. And he was not the only man to experience that feeling during those memorable days preceding the battle of Austerlitz; nine-tenths of the men in the Russian army were then in love, though less ecstatically, with their Tsar and the glory of the Russian arms.

At the end of the tragic and horrendous battle, Rostov finds himself alone with the Tsar, but like a nervous lover, cannot bring himself to approach this great man:

But as a youth in love trembles, is unnerved, and dares not utter the thoughts he has dreamt of for nights, but looks around for help or a chance of delay and flight when the longed-for moment comes and he is alone with her, so Rostov, now that he had attained what he had longed for more than anything else in the world, did not know how to approach the Emperor, and a thousand reasons occurred to him why it would be inconvenient, unseemly and impossible to do so.

Tolstoy’s description of soldier as lover stuck me as an inverted example of Ovid’s theme of Militia Amoris (“soldier of love”) that he incorporates into the Amores. The feelings of love and admiration in this context of battle deepen, I think, the anthropomorphic reality that pervades War and Peace. But, like the Homeric heroes and Ovid as a lover, Tolstoy hints that, although these men have lofty, mortal goals, things will not turn out well for them.

I just saw this post and the previous post, and you are inspiring me to follow through with my resolution to pick up War and Peace after I finish The Leopard. I have the Pevear and Lavronsky (sp?) translation. I used their translation for Anna Karenina and The Brothers Karamazov. Are you using any footnotes/endnotes to help with your reading? Does your translation have them?

I saw on your previous post that several people have recommended Life and Fate. Linda Grant has a fabulous article about reading that book that she wrote several years back in The Guardian.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am reading the Oxford World Classics translation and I really like the endnotes in it. It also has a list of characters in the front of the book and maps which really help. You are the third person to recommend Life and Fate so I must also get to that book this year! Thanks so much for pointing me to Linda Grant’s article as well.

LikeLike

Pingback: Qualis Apes: Vergil, Tolstoy and Bees |

Pingback: The Sum of These Infinitesimals: Some Concluding Thoughts about War and Peace |