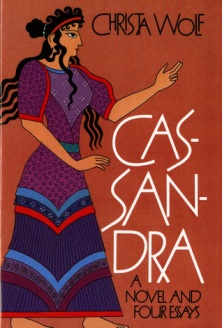

This title was published in 1983 in the original German and this English version has been translated by Jan van Heurck

My Review:

Cassandra is most famous in Greek mythology for possessing the gift of prophecy but this unique gift came with one problem: no one ever believes her true predictions. In Aeschylus’s Agamemnon, Cassandra says that she agreed to have sex with the God Apollo in exchange for the gift of prophecy, but when she went back on her promise and refused the Sun God’s advances, Apollo made sure that her prophecies would never be believed. When she predicts the future her friends and family treat her as nothing more than a babbling and a raving mad woman. I have a distinct memory of first translating the Agamemnon and how difficult Aeschylus’s Greek is to unpack. But the parts in the narrative in which Cassandra is speaking were a nice break because oftentimes she just rants and raves; the various “oi” and “oimoi” noises she makes are a welcome respite from the complex grammatical structures of Aeschylus’s sentences.

Cassandra is most famous in Greek mythology for possessing the gift of prophecy but this unique gift came with one problem: no one ever believes her true predictions. In Aeschylus’s Agamemnon, Cassandra says that she agreed to have sex with the God Apollo in exchange for the gift of prophecy, but when she went back on her promise and refused the Sun God’s advances, Apollo made sure that her prophecies would never be believed. When she predicts the future her friends and family treat her as nothing more than a babbling and a raving mad woman. I have a distinct memory of first translating the Agamemnon and how difficult Aeschylus’s Greek is to unpack. But the parts in the narrative in which Cassandra is speaking were a nice break because oftentimes she just rants and raves; the various “oi” and “oimoi” noises she makes are a welcome respite from the complex grammatical structures of Aeschylus’s sentences.

Christa Wolf’s Cassandra is an ambitious novel in that it tries to cover the entire scope of the Trojan epic cycle by telling it through the eyes of this doomed and unlucky Trojan princess. Priam, Hecuba, Helenus, Achilles, Aeneas, Troilus, Briseis, Calchas, Agamemnon, Menelaus, Polyxena and Paris, are just a few of the characters that make an appearance or are mentioned in Wolf’s narrative. Cassandra, the narrator of this story, is the daughter of Priam, King of Troy, and his first and most favored wife, Hecuba. From a very young age Cassandra wants nothing more than to become a priestess of the God Apollo and possess the gift of prophecy. But once she is given this gift she is subjected to a plethora of other misfortunes which lead to her tragic death. Wolf’s narrative is so wide-ranging and covers so many characters and actions from the Trojan saga that it is impossible to mention everything she touches on in one review. So I am going to write about the aspects of Wolf’s story that were the most striking and memorable for me.

In the original myths and stories involving the origin of the Trojan War, Paris, the prince of Troy, visits King Menelaus of Sparta and with the help of the Goddess Aphrodite, absconds with his wife Helen. In order to get his wife back, Menelaus asks his warmongering brother, King Agamemnon of Mycenae, to help him get an army together, sack Troy, and find his wife. Wolf makes her story less a matter of love, pride and recapturing a straying wife and instead makes the inception of the war more of a political issue. Priam’s sister has been taken by the Greeks and there are three separate, and unsuccessful expeditions to bring her back; on the third and final ship, Paris sets sail with the other men and when he cannot get his aunt back he takes Menelaus’s wife instead. Paris is portrayed as an arrogant and brash young man who uses the pretext of the expedition to take for himself a woman who is said to be the most beautiful in the world. Christa’s Paris is much more bold than Homer’s Paris, but in both tales Paris has no forethought or concern for anyone other than himself.

When the Greeks attack Troy, Cassandra has already seen this event coming and predicted that it will destroy her home and her family. She has a dream when she is a child that Apollo spits in her mouth and this is the sign that she can foretell the future but no one will believe her. When she has one of her prophetic visions she foams at the mouth, has fits that mimic the symptoms of a seizure and drives everyone away from her because they think she is a babbling lunatic. Cassandra’s narrative about her childhood, how she acquired her gift of prophesy, the destruction of Troy and its aftermath are all told in a stream-of-conscious narrative. Wolf’s Cassandra constantly moves around between different time periods and this cleverly reflects the anxious ramblings of her tormented mind. She oftentimes dwells on her earlier years when she was first given the ability to prophesy and became a priestess of the God Apollo. She is King Priam’s favorite daughter and her position as favorite as well as her ability to predict the future cause her to have complicated relationships with her siblings, her mother, and other men in her life.

When Troy is sacked, all of the Trojan women who survive are divided up among the Greek Kings and taken back to Greece to become their household and sexual slaves. Cassandra is taken back to Mycenae by King Agamemnon and her interactions with this narcissistic man cause her to reflect on the other complicated relationships she has had with men throughout her life. Wolf portrays Cassandra as having a great desire to be a priestess of Apollo and remain a virgin, but even her desire to remain untouched is conflicted. There is a strange scene that Wolf includes in which all of the young women in Troy are placed within the sanctuary of a temple and one by one they are chosen by Trojan youth for a ritual deflowering. It is oftentimes the tendency for non-Greek, Eastern cultures to be portrayed as being more sexually open and even promiscuous. In the Ancient Greek myths Priam is basically described as possessing a harem with multiple wives and fifty children. Even though this is not necessarily emphasized in Homer, Wolf seems to pick up on the sexual differences between the Greeks and the Trojans. When Cassandra does finally become a priestess, she puts up with the head priest visiting her nightly for sexual trysts and she endures it because she pretends she is sleeping with Aeneas whom she loves very much.

Cassandra views Agamemnon as a self-centered, rash and dangerous man who is also sexually impotent. In Cassandra’s eyes Achilles is not any better a man than Agamemnon and she describes Achilles as a murderous, selfish brute who takes what he wants, including Cassandra’s sister Polyxena. The only male in the story that Cassandra has any positive thoughts for is Aeneas, a Trojan youth who is the only hero to escape from Troy when it is burning. In the ancient Greek myths Aeneas and Cassandra are cousins but they don’t have any real connections other than Cassandra’s prediction that Aeneas will escape Troy. I am curious as to why Wolf chose Aeneas at the only male in the Trojan saga with any redeemable characteristics. The depressed, hopeless, confused, Cassandra in Wolf’s narrative becomes a completely different person when Aeneas is around. The only time when Cassandra has positive, loving thoughts are when she is around Aeneas:

At the new moon Aeneas came…I saw his face for only a moment as he blew out the light that swam in a pool of oil beside the door. Our recognition sign was and remained his hand on my cheek, my cheek in his hand. We said little more to each other than our names; I had never heard a more beautiful love poem. Aeneas Cassandra. Cassandra Aeneas. When my chastity encountered his shyness, our bodies went wild. I could not have dreamed what my limbs replied to the questions of his lips, or what unknown inclinations his scent would confer on me. And what a voice my throat had at its command.

One final male in the story that is not portrayed in a positive light is Hector, the prince of Troy and first son and heir of King Priam. In the Iliad he is, I would argue, the most heroic of the men on either side because he has a sense of honor and courage that no other warrior possesses. So I was disappointed that Wolf refers to him as “Dim-Cloud” and Cassandra remarks, “A number of my brothers were better suited than he to lead the battle.” To have veered so far off the mark from the Hector of the Iliad was disappointing to me.

When I teach about the God Apollo and Cassandra and her doomed gift of prophecy, my students always have a hard time with the fact that time and again Cassandra prophesies the truth but not a single person ever believes her. My interpretation of Cassandra has always been that she represents that person who tells us the very thing we don’t want to hear about ourselves or our actions that we continue to ignore. Cassandra is the classic case of being mad at and ignoring the person who tells us the truth and is honest but who we will cast aside anyway because the truth is too hard to bear. Wolf writes a spectacular rendition of Cassandra and brings to the forefront this allegory of ignoring our better judgement and the better judgement of others and suffering the negative consequences for it.

I could really go on and on about my impressions of Wolf’s writing and her exploration of the Trojan saga through the eyes of Cassandra. I would love to hear what other readers have thought about this book. What were the most memorable parts of the book for you? Had you read any of the original myths before encountering this books? Why do you think Wolf chose Aeneas as a companion for Cassandra? What do you think of Wolf’s rendition of Cassandra?

About the Author:

As a

As a

She won awards in East Germany and West Germany for her work, including the Thomas Mann Prize in 2010. The jury praised her life’s work for “critically questioning the hopes and errors of her time, and portraying them with deep moral seriousness and narrative power.”

Christa Ihlenfeld was born March 18, 1929, in Landsberg an der Warthe, a part of Germany that is now in Poland. She moved to East Germany in 1945 and joined the Socialist Uni

She won awards in East Germany and West Germany for her work, including the Thomas Mann Prize in 2010. The jury praised her life’s work for “critically questioning the hopes and errors of her time, and portraying them with deep moral seriousness and narrative power.”

Christa Ihlenfeld was born March 18, 1929, in Landsberg an der Warthe, a part of Germany that is now in Poland. She moved to East Germany in 1945 and joined the Socialist Unity Party in 1949. She studied German literature in Jena and Leipzig and became a publisher and editor.

In 1951, she married Gerhard Wolf, an essayist. They had two children.

In some ways she use the Cassandra myth is looking into the past to talk about the time she was in when she wrote the books

LikeLiked by 2 people

What a fascinating review, Melissa. I know the bones of the Iliad story, and I have Cassandra on my shelves. The Wolf I’ve read has been challenging but satisfying and I *am* keen to read more.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks so much. I think Wolf’s books can be enjoyed with little or no knowledge of the Iliad. She does a good job of weaving the back story into the plot.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I had no idea this was about the Greek Cassandra (I assumed the title was symbolic) – I’m now even more interested in reading it! Have you read Alessandro Baricco’s An Iliad?

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks so much, Grant! I have not read Baricco’s book, so I will have to take a look at it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I hadn’t known this was about the Greek myth. I’ve only read one Christa Wolf novel – The Quest for Christa T which I enjoyed- not sure how much this complex novel appeals though it has a fascinating premis.

LikeLiked by 2 people

It is dense, but it is a short read at only 138 pages. I would recommend it to anyone with an interest in Greek myth, especially the Troy saga.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I read this for GLM last year, and it was definitely one of my favourites. I have to admit that I wasn’t overly familiar with Cassandra’s role in the siege of Troy, and the focus on her, and the other Trojan women, made for a fascinating story 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

I am so glad to hear you liked it. I will read your review. I am so eager to see what other people think about this book!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: My Literary jouissance of 2016 |